The Road to the Dayton Peace Accords: The Art of (Im)Possible

1945 – 1992 Socialist Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia was a socialist country in Southeast and Central Europe. It consisted of six republics: Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Macedonia. Two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina, were also part of this socialist country. Orthodox Christianity, Roman Catholicism, and Islam were the dominant Yugoslav religions. Due to its non-aligned status and geographic position, Yugoslavia became one of the most strategically important countries during the Cold War, connecting the West to the East.

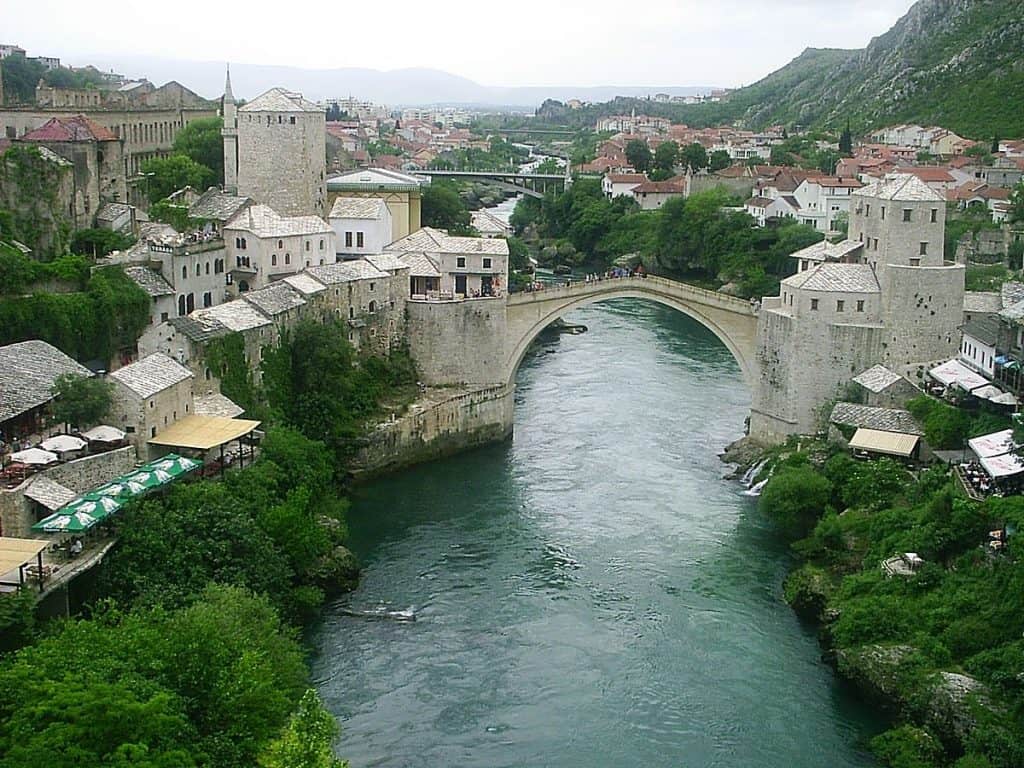

Photo credits: 1. The 16th century bridge, “The Old Bridge,” connecting Bosniak and Croat communities in the Bosnian city of Mostar has become a symbol of reconciliation and cooperation | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0.

Josip Broz Tito Dies

On May 4th, 1980, President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito died. Tito, a leader of the Yugoslav Partisans during World War II, established a communist Yugoslav state in 1945. He served as an authoritarian leader, crushing any opposition to his decades-long rule, persecuting and killing his political opponents, and ensuring no separatist movement within the Yugoslav republics and provinces could flourish and undermine his authority. Following his death, under the Constitution of 1974, the power of the presidency was transferred to a rotating presidency. The collective presidency model allowed each representative of the Yugoslav Republic to take a turn as a leader of Yugoslavia, allowing, in effect, the distribution of power among different ethnic groups and avoiding a power vacuum that most certainly would occur following Tito’s death. With decentralization, long-suppressed ethnic nationalism gradually started to dominate political discourse. Ethnic nationalism was used to erode the common identity championed by Tito, incite fear and mistrust among ethnicities, and to call for independence and soveregnity of each republic. Yugoslavia started to disintegrate.

Slobodan Milosevic Delivers Speech at Kosovo Polje

In April 1987, Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic delivered the so-called Gazimestan speech, commemorating the 600th anniversary of the Serbian Kosovo Polje battle. With already rising political tensions between Serbia and other Yugoslav republics and provinces, the speech has been seen as an announcement of the Serbian intentions and aggression fully on display during the 1990s Yugoslav conflict and especially during the Kosovo war. In essence, the speech was an extension of the Serbian grievances laid out in the 1986 Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Art (SANU). As the leader of the largest Yugoslav republic, Milosevic moved toward centralizing power while simultaneously championing Serbian nationalism and victimhood, creating a strong opposition within other republics and bringing Yugoslavia closer to disintegration.

Iron Curtain Falls

With the Eastern block’s economic struggle and desire for liberation from communism and authoritarianism, the Iron Curtain, dividing Europe and the World in two since 1945, started to crumble. From the Solidarity Movement in Poland to the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia to the Romanian Revolution, the message was clear: we want democracy, economic prosperity, and freedom. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent peaceful dissolution and disintegration of the Soviet Union, a new era of peace and liberalism began. As Francis Fukuyama famously proclaimed, “It was the end of history.” At home, with a spectacular victory in the Gulf War, a historic win over communism, and a strong commitment to international cooperation, it was time for a peace dividend, reducing defense spending and focusing more on domestic issues. After decades of post-World War II recovery and rebuilding, Europe sensed that this was a moment requiring stronger unity among European states, pledging further integration of the European continent and transforming the European Community (EC) into the European Union in 1993. While the sense of optimism dominated in Europe, Yugoslavia disintegrated, bringing war to the European continent for the first time since 1945.

Photo Credits: 1. Portrait of the President of Yugoslavia wearing his signature marshal uniform | See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons 2. Slobodan Milosevic, President of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0. 3. People using hammers and chisels to tear down the Berlin wall | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0.

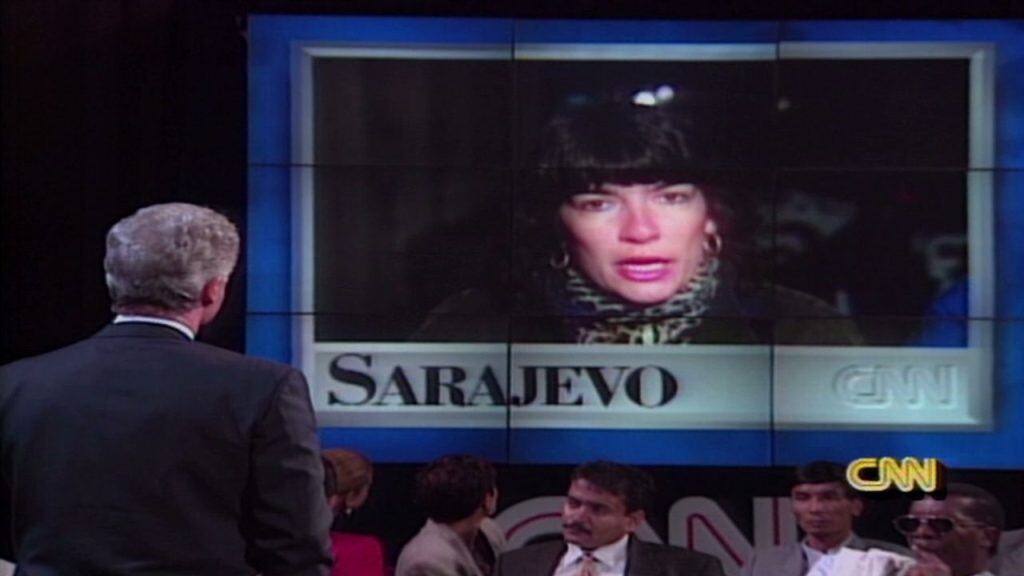

1991-1995, Early Diplomatic Efforts and CNN Effect

Europeans led early diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict in Yugoslavia. As the Luxembourgish politician Jacques Poos declared, “The Hour of Europe has dawned.” Former U.S. Secretary of State Cy Vance and Lord David Owen, on behalf of the United Nations and the European Union, and former U.S. President Jimmy Carter engaged in mediation efforts to find a solution to the Bosnian crisis. Many principles underlined in the Vance-Owen plan, including territorial distribution, were later included in the Dayton Peace Accords. With the emergence of the 24-hour news channel in the 1980s, the War in the Balkans became a “living room war” for many Americans. CNN reporters, such as Christiane Amanpour, reporting on the latest atrocities Bosnian Serbs committed in Bosnia, created powerful pressure on the Clinton administration to get more forcefully involved in resolving the conflict.

Photo Credits: 1. Former U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance served as the United Nations Special Envoy for Bosnia and Herzegovina | Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress/Bernard Gotfryd

Slovenia and Croatia Declare Independence

With a strong sense of optimism and desire for freedom all around Eastern Europe, Slovenia and Croatia, following the first direct, multiparty elections, presented their residents with a referendum on their independence. With voters in both republics voting overwhelmingly for independence, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia on the same day, June 25th, 1991.

War in Slovenia

Following Slovenia’s declaration of independence, the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) responded with force to prevent Slovenia from seceding from Yugoslavia. Slovenia, with a small Serbian population, was not of significant importance to Belgrade, and any extended conflict in Slovenia became seen as a waste of resources for JNA. After ten days of conflict, the war ended with the Brioni Accords and Slovenia’s full sovereignty and territorial independence from Yugoslavia. Belgrade then turned its full attention to a much more important political issue: Croatia.

War in Croatia

The Croatian Serbs objected to Zagreb’s territorial independence and sovereignty calls, inciting minor sabotage and skirmishes to spread fear and express disagreement throughout 1990 and 1991. Initially, Belgrade tried to stop Croatia’s departure but, failing to do so, changed its strategy to preserve the territory where the Serbian population lived. With the help from the Yugoslav military (JNA), the Croatian Serbs established their quasi-state, the Republic of Serbian Krajina, in 1991 within the territory of the newly independent Croatian state, expelling Croats and other non-Serbs out of its controlled territory while also engaging in a campaign of ethnic cleansing. In November 1991, Belgrade forces, aided by Serbian paramilitary forces, captured the city of Vukovar after an 87-day siege, massacring prisoners of war and civilians and expelling survivors out of the town. In January 1992, the ceasefire was signed, ending the intense fighting, establishing war lines, and deploying the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) to the region. With the Krajina Serbs controlling almost one-third of the Croatian territory, Croats moved their focus to retaking the lost parts of their country.

Bosnia Declares Independence

With Slovenia and Croatia declaring independence, the most ethnically diverse Yugoslav republic, Bosnia and Herzegovina, faced an inevitable question: to remain in the Serb-controlled Yugoslavia or declare independence. In early Spring 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina held its referendum on independence, and in soon after, it officially declared its sovereignty. The Bosnian Serbs boycotted the referendum and, anticipating overwhelming support in favor of the independence, established on January 9, 1992, Republika Srpska, the Serb Republic, over the parts of Bosnia to protect the interests of Bosnian Serbs. A mountain village, Pale, near Sarajevo, served as a headquarters for the Bosnian Serb military leaders.

Bosnian War

The aggressor, Bosnian Serbs, engaged in ethnic cleansing, rape, and expulsion of Bosniaks and Croats from the Serb-controlled territory throughout the war. The Bosnian Croats 1991, established within Bosnian territory a Republic of Herzeg Bosnia, claiming the areas where Croats lived. While both Bosniaks and Croats fought the same enemy, the Bosnian Serbs and Belgrade, the tensions between them grew, and they eventually fought each other, starting what is known as “war within a war.” From October 1992 to March 1994, the two militaries fought sporadic battles; eventually, a ceasefire was agreed upon, and the “allied” approach toward the common enemy was resumed. In 1994, Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats signed the Washington Agreement, combining their territory and creating the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Losing control over the rogue Bosnian Serb leadership and under tight economic pressure, Slobodan Milosevic started to look for a way to reach a peace in Bosnia. After the intensive American-led shuttle diplomacy in November 1995, the warring parties agreed to a peace agreement to end the war in Bosnia.

Siege of Sarajevo

From April 5, 1992, to February 29, 1996, Sarajevo was under the Bosnian Serb siege. The Bosnian Serbs controlled the surrounding hills, assaulting the city with artillery and snipers and creating a humanitarian crisis in the city, with food, electricity, and water being scarce. Early American diplomatic efforts focused on how to deliver humanitarian aid to the town and other blocked areas of the war-torn country. In June 1992, the UN took control of the city’s airport to provide much-needed humanitarian aid to the besieged city. Between March and June 1993, the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina constructed a secret tunnel under the Sarajevo airport, connecting Sarajevo to the Bosnian-controlled territory. The tunnel provided the besieged city an escape route and corridor for humanitarian aid and embargoed arms. While the Bosnian army was able to defend the city during the siege, it was unable to break it. The siege ended following the Dayton Peace Accords.

Srebrenica Genocide

In July 1995, the Bosnian Serb forces, commanded by Ratko Mladic, killed more than 8,000 men and boys in the area of Srebrenica. Srebrenica, like Sarajevo, was under the Bosnian Serb siege for three years, with many Bosniaks expelled by the Serb forces taking refuge in the town. In 1993, the UN declared Srebrenica a “safe zone,” with UN forces protecting the enclave. At the time of the massacre, the lightly armed Dutch soldiers were protecting the area. During the Serb offensive, refugees from Srebrenica moved closer to the Dutch positions at nearby Potocari to seek protection from the coming Serbian forces. The Dutch, unable to secure quick air support to stop Bosnian Serb advances, were unable to defend the enclave. Srebrenica was the worst massacre in Europe since World War II, and it was a wake-up call for the West that something had to be done to end the conflict in the Balkans.

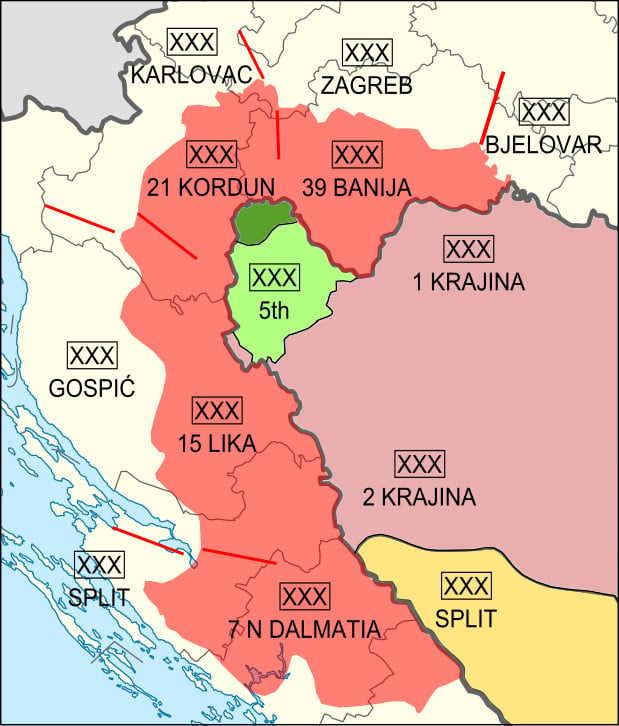

Operation Storm

Operation Storm was the last major battle the Croatian Army fought against the Serb forces and was the decisive victory for the Croats. Between August 4th and August 7th, the Croatian Army was able to liberate almost all of its territory under Serb control, unite Croatia into one geographic unit, and dismantle the quasi-state of the Republic of Serbian Krajina. The operation effectively ended the siege of Bihac in Bosnia and provided Croats and Bosnians with momentum against the Serbian forces. The operation shifted the balance of power on the battleground, in favor of the Croatian and Bosnian forces, providing a much-needed opening for diplomatic discussions on how to end the war. At the same time, in Washington, President Clinton was meeting his national security team and determining final strategy on how to end the conflict.

Photo Credits: 1.The island of Bled, Slovenia | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. 2.T-55, a Yugoslav tank, hit by the Slovenian anti-tank system during the Slovenian ambush near Rozna Dolina, Nova Gorica | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0. 3.Shelling of the old town of Dubrovnik during the war in Croatia | Bracodbk. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0. 4.United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) forces during the Bosnian War | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. 5.Sarajevo Rose has become a well-known memorial to those who perished during the siege of Sarajevo. Around 200 “roses” in the city depict places where mortar shells exploded | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0. 6.The siege of Sarajevo was a humanitarian catastrophe, with many resources scarce and non-existent | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0. 7.Srebrenica Genocide Memorial | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0. 8. Map showing the Operation Storm and the Croatian army corps involved in the operation | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

August 7, 1995, US Shuttle Diplomacy Begins

Under growing pressure to lift an arms embargo and witnessing a growing Serbian ethnic cleansing campaign in Bosnia, the Clinton administration decided it had enough. In August 1995, they developed a strategy known as “Endgame.” The President appointed Assistant Secretary for European and Canadian Affairs Richard C. Holbrooke to lead the negotiations with the Balkan leaders. Holbrooke and his team embarked on intense shuttle diplomacy in the region, visiting all three Balkan capitals in search of an agreement to end the war. In contrast to the previous negotiations efforts, Holbrooke had NATO’s air support at his disposal, allowing him to use both a carrot and stick approach to pressure the parties to the negotiations table. While the Bosnian Serbs continued to test the Western resolve, Holbrooke effectively pressured Milosevic to force Pale into an agreement, in essence, finding a trusted partner in the Serbian President. With the cease-fire in place, the reopening of Sarajevo airport, and various agreements in principle, Holbrooke brought parties to Dayton, OH, to finalize the peace.

Photo Credits: 1. The Sarajevo Tunnel was built in 1993 to link the besieged city with the Bosnian territory | Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Peace Talks in Dayton, OH

In November 1995, representatives from Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia met at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, for proximity talks to end the conflict in the Balkans. The base’s closed setting allowed Holbrooke and his team to control the press, ensuring that no party could leak information to the media and obstruct negotiations. As expected, negotiations went back and forth and were filled with disagreements, with Holbrooke and his team running from delegation to delegation, seeking compromise and effectively utilizing backchannels to achieve an agreement. After finalizing the federation agreement between Bosnians and Croats and Eastern Slavonia issues in the first eleven days, the conference focused on ending hostilities in Bosnia and structuring political and territorial structure that all three ethnic groups would be satisfied with. Following intense map negotiations in the final days of the conference, peace was reached on November 21, 1995. Bosnia became a country consisting of two entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, with the fate of Brcko district scheduled to be decided during the arbitration. The Dayton Peace Agreement was formally signed in Paris, France, on December 14, 1995.

Peace Implementation in Bosnia and Herzegovina Begins

The Dayton Peace Accords, consisting of 11 annexes, created a road map for everlasting peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Annex 1A/B pertained to military affairs and implementation under NATO and later European supervision. Annex 4 outlined the Bosnian constitution, and Annex 10 created the Office of High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, tasked with the civilian implementation of the Agreement. Other international organizations, such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), were tasked with election monitoring. Under the watchful eye of the internationally composed Peace Implementation Council (PIC) and the UN Security Council, peace implementation began following the signing of the Accords in December 1995. The implementation mission continues to this day.

Photo Credits: 1. The three Balkans presidents initial the draft of the Dayton Peace Agreement on November 21, 1995, in Dayton, Ohio | Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Air Force 2. Bascarsija, Sarajevo’s Old Town | Michal Gorski. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.