Images of the U.S. military in Vietnam are part of the American consciousness. But these images are only part of the story. Often the lives and sacrifices of USAID workers are overlooked. They too made great contributions, joining with military personnel to deliver supplies to locals, promoting development in dangerous areas, and working with hamlet chiefs and ordinary civilians. Some USAID workers even lost their lives. Sidney Chernenkoff’s first overseas assignment with USAID was in Vietnam at the height of the war. His service is an excellent example of the complexity and value of USAID’s contributions to a war that remains controversial long after it has ended.

Chernenkoff initially joined USAID after spotting an advertisement in the San Francisco Chronicle that said the agency was hiring for service in Vietnam. He was interviewed, scored highly on a language aptitude test, and was sent to Hawaii for six months to learn Vietnamese. He then boarded a plane in March 1967 and arrived in Vietnam just as the war was entering its most intense phase. Chernenkoff worked as a part of the CORDS (Civil Operations and Rural Development Support) program in the town of Tuy Phuoc, about 300 miles northeast of Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City).

Chernenkoff received a BA and an MBA from the University of California, Berkeley. Apart from his posting in Tuy Phuoc, he worked in Saigon (also in Vietnam), Washington, El Salvador, and Sudan.

Sidney Chernenkoff’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on August 21, 2017.

Read Sidney Chernenkoff’s full oral history HERE.

For more Moments on Vietnam, click HERE.

Drafted by Ashley Young

Excerpts:

“I experienced a lot of happy but also brutal scenes and in many ways grew up and matured [in Tuy Phuoc].”

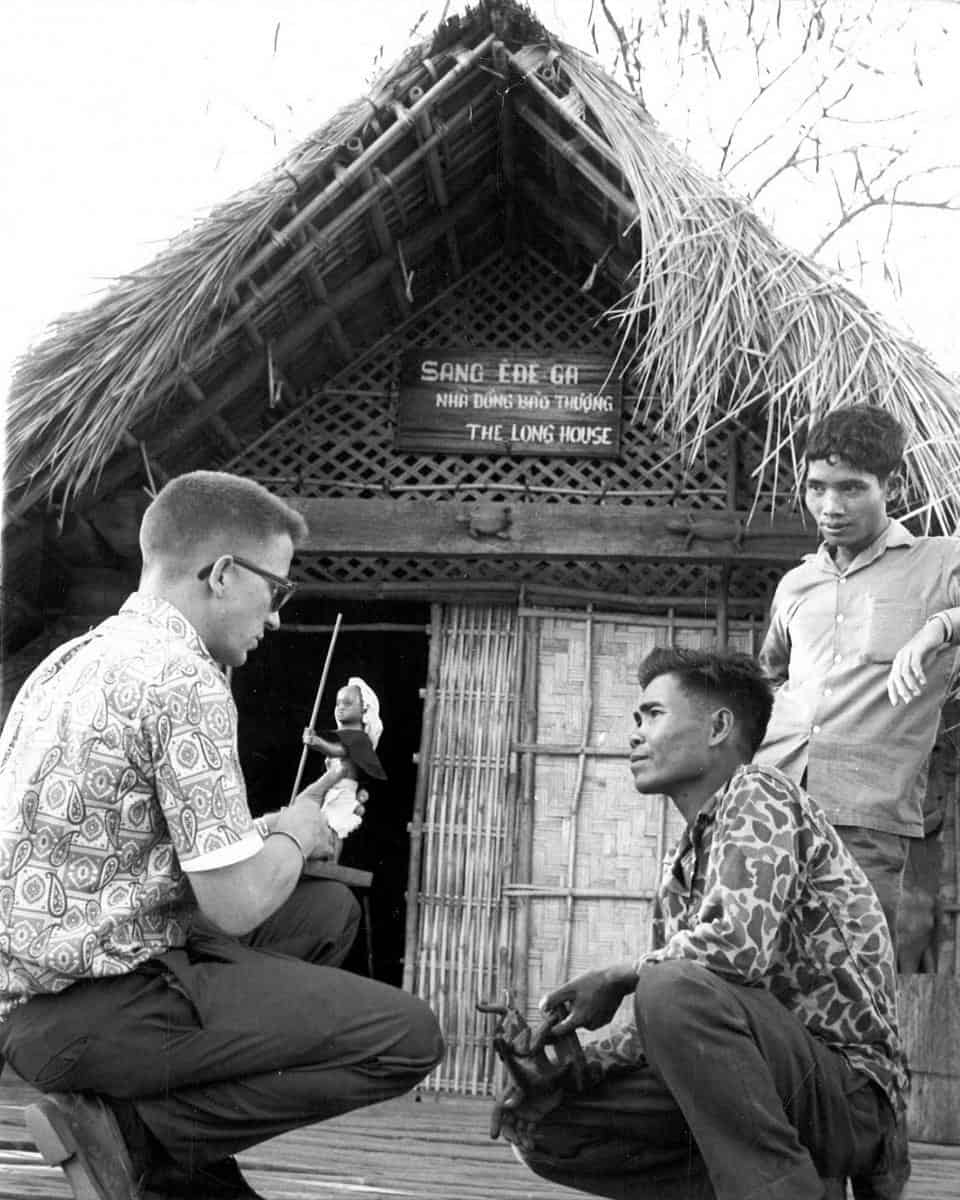

The initial mission in Tuy Phuoc: We planned to work within the framework and resources of the nationwide joint U.S.-Vietnam pacification program which was aimed at improving the lives and security of the rural Vietnamese people. This included civilian efforts to construct or repair schools, village offices, irrigation, roads, as well as provide training for teachers, city managers, and farmers and assist refugees. Upon arrival, we expected to be sent to provinces and districts throughout Vietnam, and that we would be working closely with the U.S. Army MACV (Military Advisory Command Vietnam) advisory teams. These were specially trained, typically eight or nine-man units, advising Vietnamese province and district chiefs on military affairs. At the district level, they were led by a major and a captain, two lieutenants, several sergeants, a medic, and a radio operator. These guys lived in the district compound and trained local forces how to fight the Viet Cong (VC). We would join a MACV unit and carry out civilian projects working with the district chief and his staff. I was assigned ultimately to Tuy Phuoc district, Binh Dinh Province on the coast of central Vietnam. I worked side by-side with the MACV unit, coordinated with them and ultimately ended up living with them, advising the district chief on all these matters that were not military. . . . The officers and enlisted men came and went. But I stayed and over time became the most experienced officer. I experienced a lot of happy but also brutal scenes and in many ways grew up and matured there. . . .

“The contrast between me being treated simply for diarrhea and the gravely wounded treated across from me was so stark and would have been funny if it were not so serious. It immediately brought the reality of the war in focus for me.”

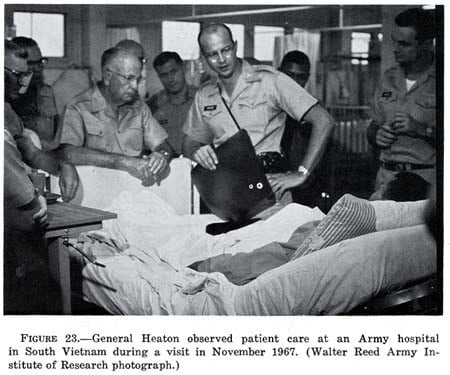

Eyes opening to war: One incident worth mentioning I think encapsulated the craziness of the war and my introduction to it. Before arriving in Qui Nhon, I had been sick for over three weeks having eaten something in Saigon that gave me persistent diarrhea. Upon arrival in Qui Nhon, I suffered quietly then finally told a colleague. He took me directly to the Army military hospital where I took seat along the side of the long barracks-like building where a few GIs also waited their turn to see a doctor. We all had minor ailments. Directly across from us perhaps 10 feet away, was a row of about ten emergency beds. It was quiet when I arrived, but after about ten minutes, an alarm went off that helicopters were arriving. They landed and one by one unloaded wounded U.S. Army soldiers groaning and crying in pain. Female nurses immediately attended to them, trying to calm them done verbally and treating their wounds. More wounded GIs arrived and were treated, using up all the beds. It was quite chaotic and in stark contrast to the ailments I and the others in line suffered. Meanwhile, we quietly inched up towards our own doctor as [he] called out next patient. The contrast between me being treated simply for diarrhea and the gravely wounded treated across from me was so stark and would have been funny if it were not so serious. It immediately brought the reality of the war in focus for me. . . .

“I learned that the more we do for the Vietnamese, the less they will do. Conversely, the more you give them to do, the more they’ll do.”

Lessons from Vietnam: I remember the first task I had in the District was distribution of supplies. Once a week, Vietnamese hamlet and village officials would come to the MACV compound and a sergeant would distribute, according to specific plans, food, cement, or steel enforcing bars for construction. There was a warehouse in the compound where this stuff would be delivered and stored. These were seen as U.S.-owned goods and we distributed it. The sergeant said we’re so glad you’re here, now you can do this. The warehouse was a complete mess, just a complete pile of bags randomly placed, metal on top of bags, broken items everywhere. It quickly became apparent to me that this was really not right because this stuff actually belongs to the Vietnamese. I said to the major that I don’t think we should be doing this, the Vietnamese should. My Hawaii training kicked in, which is that the Vietnamese should do as much for themselves as they can. So, I wrote a letter to the District Chief, whose name unfortunately I forget, to make it formal that this is his stuff, and from now on they would make distributions. He agreed and the village chiefs began to go to the district chief and who quickly organized a distribution system. About a month later Major Wright and I took a look at the warehouse. It was completely cleaned out, things were in the proper places, the bags were neatly stacked, and there were proper records. Because we had turned the supplies over to them made a huge difference on how it was accounted for, who got it and when and how it was carefully protected. This made a lasting impression on me and a proxy for how the war itself was being conducted. I learned that the more we do for the Vietnamese, the less they will do. Conversely, the more you give them to do, the more they’ll do. We did too much of the work and the fighting….

“Everybody was convinced Tuy Phuoc was such a secure place, but we were like sitting ducks. People were killed unnecessarily as it was totally unexpected.”

Increasing dangers: My first six months in Tuy Phuoc were very peaceful and nothing regarding security happened. I spent most of my time visiting on-going or planned projects. Just before Christmas 1967, I was asked to go to Seattle to recruit people for USAID to come to Vietnam for jobs just like mine. I flew back and with a couple other USAID officers spent some time with the local press, radio, and TV touting the great work available in Vietnam. This gave me the opportunity to see my parents for Christmas and visit friends in California, ensuring them all how safe it was for me in Vietnam. But while I was away, the Viet Cong surprised everyone one night and largely over-ran the compound, killing the District Chief, in front of his family, and other RF defenders. Our MACV medic was shot through the chest but survived. The VC blew a hole in the side of the building next to my sleeping quarters. My parked Scout was completely shot up. They were eventually driven out with help from group of South Korean military advisers who had just arrived for a few days of training. But things had changed dramatically.

Q: Was this part of the Tet Offensive?

CHERNENKOFF: No, it was a month before the Tet Offensive. . . . The Tet Offensive occurred on January 31, about six weeks after we were attacked. . . . It was almost like a rehearsal. And we were shocked. Everybody was convinced Tuy Phuoc was such a secure place, but we were like sitting ducks. People were killed unnecessarily as it was totally unexpected. Major Wright was very depressed because he was told the back area that was supposed to be mined, apparently wasn’t. The VC just walked in. Worse yet, he was interviewed a few weeks earlier by Senator Birch Bayh from Indiana giving him a highly positive report on our district. This attack got a lot of attention throughout Vietnam, right when we were supposed to be winning.

“Hospital error killed him. And his name is on the Vietnam Memorial simply killed in action. That was a tragic thing.”

Tragic losses: On a quiet afternoon about 4:00 or 5:00 pm, I was sitting in the MACV common area. There was a lot of noise outside when a jeep pulled up. Major Yaden walked in and was covered with blood. He had been hit with shrapnel all over his body and was bleeding in numerous areas. He and Major Tue had gone out to look at a nearby bridge that was being protected by Popular Forces (PF). These were troops from hamlets who were the lowest level of uniformed military forces. They didn’t have much training and they didn’t go very far from their hamlets, just a sort of low-level militia. Somebody had put a hand grenade, pulled the pin, put it under a sandbag and put the sandbag in a place where someone would eventually move it. They just happened to visit this bridge, thought everything was okay, and then somebody, and maybe it was the major, picked it up and the hand grenade went off. Major Yaden was hit with shrapnel in his face, his stomach and other places. He could walk in but immediately laid down, and he was in a lot of pain. And then the District Chief walked in. He too had been injured, mainly his right thumb. And then one of the sergeants, Sgt. Lopez, walked in. He was in a bit of shock and injured too. He had a lot of shrapnel wounds and was shaking. The injured PF were taken elsewhere. Immediately, we called a medevac helicopter. The helicopter landed directly in the compound, which it never did before, to take the two Americans. I helped carry the stretcher to the chopper. We never saw Major Yaden again, though he didn’t die. After surgery, he was sent directly back to the U.S. from the hospital. We packed his stuff up and shipped it away. I visited the District Chief in a Vietnamese hospital. He was not too badly hurt but he had a pretty bad injury to his right thumb. Sgt. Lopez was assigned to U.S. Army hospital in Qui Nhon. When I went to visit him, he was just lying in his bed babbling. I thought this can’t be right because he only caught some shrapnel in a few places, and he was talking coherently when he was airlifted. So, I asked the nurse what happened. She said well, he’s going to die. She said during the operation they had a bottle of oxygen used for him during surgery and the oxygen bottle went dry. He was without oxygen for an extended period of time and suffered permanent brain damage and he did die. . . . So, hospital error killed him. And his name is on the Vietnam Memorial simply killed in action. That was a tragic thing. He was a good guy, a nice guy. . . .

“Luckily, I learned that the U.S. Army would give me money for such purposes if I just asked for it.”

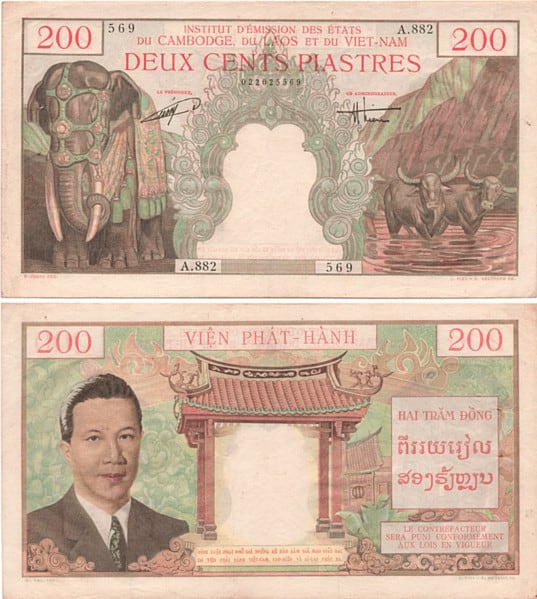

Rebuilding Vietnam: Often we would rebuild schools, roads, village offices, small bridges that had been destroyed in battles before I arrived. Sometimes it was new construction to improve roads or improve agriculture with seeds and equipment. From U.S. sources, we would order the cement, iron, and other items and get them to the villagers who needed them. We would go out and, even as tall as I am, would ride on the back of a motorcycle with Lt. Ngoc driving far off main roads to look at hamlets that were damaged, to find out what was needed, including helping refugees. We reacted ad hoc to the problems at hand and we had lots of resources. On one occasion, refugees from an eastern area told us that they wanted to go back home to reconstruct their homes and lives. Major Tue and I met with several hamlet chiefs who said they needed cash not materials as there were a

variety of needs. We thought this was acceptable. Luckily, I learned that the U.S. Army would give me money for such purposes if I just asked for it. So, I did, for $10,000 in cash. It was quite a large amount of money then. I went to an Army financial office, got approval and a check for it and went to a designated local bank to get $10,000 equivalent in Vietnamese piasters, which today might be perhaps $100,000. I gave the money to Major Tue and we met with the hamlet chiefs. At the first meeting, the village chiefs were not prepared to describe their needs in detail and just wanted the money. To his credit, Major Tue sent them home and said come back when they can list in writing their needs and a budget. They did and he doled out a certain amount of cash. We just made-up what to do; that was the solution. There was also some permanent refugee housing that had to be built. Some folks came from Saigon to help us get it going and we helped to construct permanent housing for permanent refugees. While it was under construction, I was informed by a civilian Vietnamese at the District Office that the builders were shorting on the cement to keep some for themselves. Indeed, it was true. I even shook a wall and it fell, shocking those present. The District Chief admonished me but I think he was embarrassed. Nevertheless, construction quality improved. . . .

“I . . . left Tuy Phuoc with some sadness. . . . Vietnam has a special place in my heart.”

Moving On: About September 1968, I started to think maybe I’d been out in the field long enough—it was almost a year-and-a-half. I applied for a position in Saigon at MACV Headquarters, or Pentagon East, in what was then called the Evaluations Branch. The Branch did field trips and reports for the DepCords and other senior officials. It was run by Craig Johnstone, a State Foreign Service officer. I was selected and in September 1968, left Tuy Phuoc with some sadness. . . . Vietnam has a special place in my heart.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, University of California, Berkeley 1958–1962

MBA in Marketing, University of California, Berkeley 1963–1965

Joined the Foreign Service 1966

Oahu, Hawaii—Vietnamese Language Training 1966–1967

Qui Nhơn, Vietnam—CORDS Deputy District Adviser 1967–1968

Saigon, Vietnam—CORDS Evaluations Officer 1968–1971

Washington, D.C., U.S.A.—Desk Officer for Latin America Bureau 1971–1976

San Salvador, El Salvador—General Development Officer 1976–1978

Washington, D.C.—Program Officer for Near East Bureau 1979–1983

Washington, D.C.—Officer-in-Chief for Somalia and Sudan 1985–1987

Khartoum, Sudan—Assistant Director for Program & Policy Development 1987–1988

Washington, D.C.—Director for the Office for South Asian Affairs 1991–1996