Few get the chance to leave their mark as a record holder. Beatrice Bishop Berle certainly did just that. In the mid-1940s, Beatrice Bishop Berle administered the first dose of penicillin in Brazil’s history. Her husband, Adolf Berle, Jr., was the U.S. Ambassador to Brazil from 1945–1946. Spouses of ambassadors play a considerable role in their given host country, whether it be fostering relations amongst government officials or looking out for the well-being of the embassy staff. In this regard, spouses do not necessarily trail their Foreign Service partners (as the moniker “trailing spouse” would suggest), but rather lead and contribute to American diplomatic practice through their formal and informal duties.

Adolf Berle Jr. was an original member of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust.” The “Trust” was a group of policy experts who offered advice and guidance to FDR during his presidency. Adolf Berle Jr. was instrumental in crafting FDR’s First New Deal in 1933. Later in his career, Adolf Berle Jr. was assigned to the State Department as Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs. When Adolf Berle Jr. became U.S. Ambassador to Brazil in 1945, Beatrice Bishop Berle used her newfound connections to become an unpaid volunteer at a hospital in Rio de Janeiro. Her experience in the asylum ward meant that she met and knew those Brazilian citizens she would not have met at typical diplomatic events. As a practicing physician in the United States, Beatrice Bishop Berle offered vital assistance to the local ward and learned about parasitic diseases like bilharzia that affected the local community. At the local hospital in Rio, Beatrice made history by administering penicillin for the first time to two patients with pneumonia.

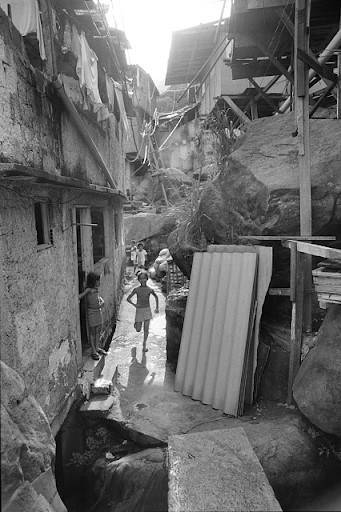

In addition to Beatrice’s time spent at the local ward in Rio de Janeiro, she also sewed for children living in local favelas (slums) and patients at the hospital under a volunteer program called “Voluntarias.” Sewing machines were set up in the embassy and were financed by Beatrice’s friends and close connections within the community. During her brief tenure in Brazil, Beatrice Bishop Berle truly exemplified the qualities of a Foreign Service spouse; a partner who uses their quasi-official role to demonstrate and contribute to strong American leadership and cooperation while abroad, ultimately enriching the work and functions of the diplomatic service.

Beatrice Bishop Berle’s interview was conducted by Jewell Fenzi on September 9, 1989.

Read Beatrice Bishop Berle’s full oral history HERE.

For more moments on Foreign Service Spouses click HERE.

Drafted by Jonathan Adams

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“This was really a wonderful experience, because I gave the first penicillin.”

Volunteer Work:

I made a number of Brazilian connections, among them the president—whose name I can’t recall—of the board of the Santa Casa in Brazil, the Rio city hospital in downtown Rio. All Portuguese colonies had “santa casas,” which the Infantas had founded; a combination of asylum and acute hospital. So in 1945 the directors arranged that I could go to the ward, provided this was a non-paid affair. This was a really wonderful experience, because I gave the first penicillin. At that time penicillin was beginning, and I remember going down in the evening to the Santa Casa and delivering penicillin to two people with pneumonia.

The fellow who ran the ward was a nice fellow, who I continue to see now, who had done his residency during WWII at Ann Arbor, Michigan. But I was not allowed to practice, because there was a law saying that foreign physicians couldn’t practice. I was allowed, however, to go there and help out. I practiced in the sense that I took care of people on the ward. So I learned a great deal about Brazilians whom you don’t meet at embassy cocktail parties; and also about parasitic disease. So that later when I was at Maceió [Maceió is the capital of the state of Alagoas in Brazil’s northeast.], [for Project Hope in 1973] I knew already quite a little about the disease that was prevalent up there, bilharzia. . .

While I was working at Santa Casa, I put together a rather interesting text. It’s called, “The Book of Preventive Medicine.” In the Santa Casa, they had seminars, and I organized this as a text for common diseases to be used in the interior. A friend agreed to publish it. We had lectures by a number of Brazilian physicians. Believe it or not, I wrote the chapter on penicillin, which shows you how long ago this was, when penicillin was new. Then, we got a very good expert to make an outline of how to make privies. We had someone else write about tropical diseases. He was a parasitologist, one of those scientists who likes to account for every microbe. But I felt that the privy was a really good innovation for the interior––to keep you from getting amoebas and other parasites. A Brazilian sponsored the book, got the printing, and so on.

“Seeing Brazilians didn’t seem to be very high on the list, except for the “gran finos””.

Sewing for the Favelas:

He [Ambassador Jefferson Caffery] socialized with a few of the “gran finos” but on the whole he was not a man of the people in any sense. Of course, the diplomats weren’t all that way. I could tell you of one whom I liked who was a consul in São Paulo, whose name I can’t recall [perhaps Cecil Cross]. What I’m saying is, I wouldn’t indict them all, but I think the diplomatic service was much more structured. The whole corps was much smaller, and therefore the few diplomats saw each other all the time. And of course Rio was a much smaller town, then. Seeing Brazilians didn’t seem to be very high on the list, except for the “gran finos”. The French word for cognac is fin, so the “gran finos” were elegant, wealthy people who moved in the cognac circle. I should mention how I got the idea of starting the “Voluntarias.” That was quite an affair. We had with us this wonderful nurse, Hagie, who had been Peter’s child nurse and who was still with us. She was an RN [Registered Nurse] and children’s nurse. By now our children were grown up and she wanted to do volunteer work. So she went up into the favelas [slums] and came back horror struck at how cold the children were; it was June or July. She said, “It’s an outrage.” So at that point there developed out of that what Adolf called the equivalent of his mother’s sewing circle when they were ministers outside of Boston.

So in the Embassy ballroom we set up a whole bunch of sewing machines, and the Baronesa de Bonfim, an older woman of impeccable social standing, and others of her circle came one day a week and whirled away on their machines. They did have some concern for the poor but it became, also, “the thing to do” to come to the Embassy to sew. We sewed mainly for the hospital—layettes for infants, and so on. The project was financed by the women. Singer gave us the sewing machines. The only refreshments served were cafezinho [coffee] and a few cookies; nothing else. This was serious business! And it still goes on.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA, Vassar College 1923

MA in History, Columbia University 1923–1924

MD, New York University 1938

Husband joined the Foreign Service 1938

Washington, D.C., U.S.A.—Husband Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs 1938–1944

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil—Husband Ambassador to Brazil 1945–1946

Santa Casa, Rio City Hospital, Brazil—Volunteer 1945–1946