Bhumibol Adulyadej, also known as Rama IX, was the ninth monarch of Thailand and the longest-serving head of state in the world at the time of his death in October 2016. Beloved by his people, he was also a friend of the United States. Ambassador David Lambertson recalled his experiences with King Bhumibol and other members of the royal family in a 2004 interview.

Bhumibol Adulyadej, also known as Rama IX, was the ninth monarch of Thailand and the longest-serving head of state in the world at the time of his death in October 2016. Beloved by his people, he was also a friend of the United States. Ambassador David Lambertson recalled his experiences with King Bhumibol and other members of the royal family in a 2004 interview.

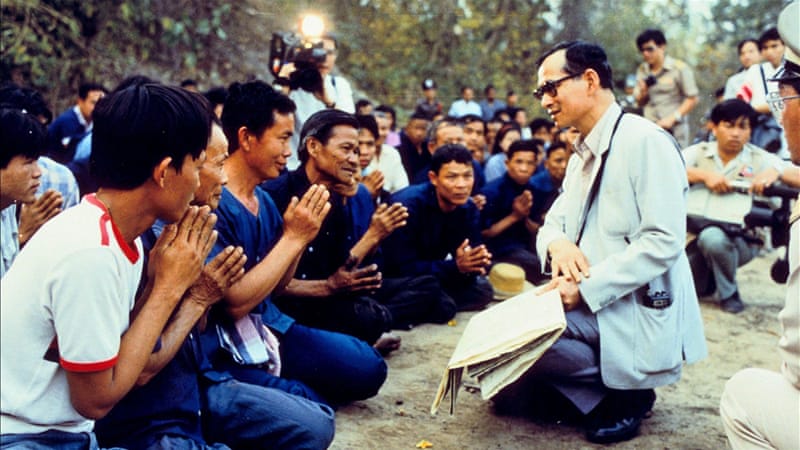

Bhumibol’s reign began in 1946. A coup in 1957 ushered in a series of military dictatorships until Thailand began to democratize after protests in 1992. The king played a key role in democratization and what would be termed “The Crisis of 1992,” and intervened after violence and riots threatened to start a civil war. After the king’s intervention, Thailand held a general election and established a civilian government. Bhumibol was highly respected and extremely popular among his people.

To read Ambassador Lambertson’s full oral history or the Thailand Country Reader click these links.

After his death in October 2016 at the age of 88, thousands of black-clad members of the public lined the streets in Bangkok. Many thousands more took part in the king’s cremation and a five-day funeral ceremony that concluded on October 26, 2017.

David Lambertson was the U.S. ambassador to Thailand during 1991-95, at the height of the democratization crisis. Ambassador Lambertson previously Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), Medan, Paris, Canberra and Seoul. Below is an excerpt of his interview, conducted by David Reuther in 2004.

“The king stepped in just in time”

LAMBERTSON: He’s the world’s longest serving monarch. Just ahead of Queen Elizabeth. He’s also the only king ever to have been born in the United States, in Boston while his father was studying at Harvard Medical School. He’s a very interesting man and I came to admire him a great deal. He has immense influence, and uses it very carefully. He seems to know when to act and when to husband his influence and over the years he’s played his cards very skillfully and to good effect. I think he played and is still playing a very constructive and important role in Thailand.

So in the spring of 1992 an election was held, I believe in March (while I was in the United States on that ambassadors’ tour). The conservative, traditionalist parties collectively won a majority of the seats and their first choice as Prime Minister was Narong Wongwan, an upcountry politician, long and unfavorably known to the United States. We were quite sure he was a drug trafficker. I’d seen the evidence and did not doubt that he was guilty. In naming him as a trafficker, we basically made it impossible for him to be prime minister. This was highly publicized in the United States. The State Department spokesman noted that if Narong were appointed prime minister, he wouldn’t be able to travel to the United States, so that would have been something of a handicap for him. In any event the coalition dropped him and named General Suchinda – the head of the army and one of the men behind the coup the previous year – as the new prime minister. This sparked widespread opposition in Thailand. It wasn’t just young people protesting the military having in effect extended themselves in power. It was an impressively middle class democratic uprising, such as had not happened for a long time, if ever.

As street demonstrations mounted [in 1992], the army was called in to preserve

order and there were confrontations between demonstrators and soldiers. There were ugly scenes of people being beaten with rifle butts and this inflamed passions all the more within the so-called “democracy movement” and tensions rose quickly. Things really came to a head in one night’s confrontation near the Democracy Monument when the army fired on demonstrators and killed many of them – perhaps one hundred. It was the bloodiest night in Thai political history, at least since the early ‘70s. And it was an evolving situation in whichwe, the United States, had an opinion and an interest. We didn’t like the idea of Suchinda naming himself prime minister. We didn’t like the idea of the army moving in in a ham-handed way. We were hoping that Thai politics would continue to evolve in a democratic direction.

The king stepped in just in time [in May of 1992] to prevent what could have been an even greater loss of life than had already occurred. I was very interested in what the King might be thinking of doing. I didn’t seek an appointment with the King. I did contact his senior advisors, however, to try to have some indication of what the King might be preparing to do.

They were noncommittal. It turned out that the King proved to be very much on top of things and at the crucial moment did intervene. The crisis was resolved when the King invited Suchinda and General Chamlong to come to the palace for an audience, which was televised live. General Suchinda and General Chamlong approached His Majesty on their knees, the King declared that the situation had gone on long enough and was displeasing him, and it essentially ended right there. There were no further demonstrations, no further confrontations between the army and civilians, and within a few days Suchinda stepped down and Anand was appointed yet again to run another government to prepare another election…

“Very simple. Very dignified.”

LAMBERTSON: I have great admiration for the King. He has played an important and positive role in Thailand’s evolution over the last 50 years and more. One of the interesting initial aspects of my interaction with the royal family was the fact that my presentation of credentials took place earlier than it might have. The Foreign Ministry and royal household arranged the presentation promptly because they wanted me to be accredited prior to the visit to Bangkok of the Emperor of Japan, which came just a few days later. It was an interesting courtesy.

…In Thailand credentials are presented to the king at his palace – Chitlada Palace, an unassuming, Victorian-looking building, a long distance from the Grand Palace. The Thai send a car to pick you up to take you there. It’s not a carriage, but an old yellow Mercedes, one of the king’s Mercedes. So I rode over there, with an escort from the palace, went into the palace, waited a few minutes in a foyer downstairs and then was told that all was in readiness.

While I was waiting I was briefed on what to do: you walk into this rather long narrow room, the king is standing at the far end of it, you make a sharp left turn and walk toward him and stop six feet away from him. He greeted me and I greeted him. I read my speech, and he read his speech. We shook hands, as I presented him my credentials. We conversed for a few minutes and then I took my leave which entailed backing up while still facing him for at least a number of paces and then turning around and walking out. There were only one or two other people in the room. Very simple. Very dignified…

LAMBERTSON: [The Emperor of Japan visit] was our first experience of a State dinner in Bangkok and it was a magnificent spectacle. The Thai probably put on ceremonies more elegantly than just about any other people in the world. A State dinner at the Grand Palace in Thailand is really something to behold. In any event, at the beginning of the evening, the diplomatic corps files through in protocol order and shakes hands with His Majesty and with the Emperor standing beside him – so Sacie and I have now shaken hands with two Japanese Emperors. Thereafter the diplomatic corps ends up at the other end of this very long room, and the King and the Emperor are still in their places and people are selected to go over and engage in conversation.

The first person chosen was me, the most junior member of the diplomatic corps, and I was asked to cross the room and converse

with their Majesties, the King and the Emperor. I did that, and I don’t remember at all what we talked about. We talked for five minutes, mostly small talk I suppose. I thought it was most interesting and intriguing that I was the one chosen to do that.

Being the American Ambassador in Bangkok is special. I saw the King on such occasions. I saw him on various other ceremonial occasions when he presided. I came to feel that I knew him and that he knew me. I never called on him by myself. Maybe I should have, but I didn’t. I saw him in the company of senior, important visitors from the United States, and then frequently on those various ceremonial occasions.

“Both the King and queen are accustomed to late evenings”

LAMBERTSON: I saw much more of the Queen. Sacie and I traveled with her to the United States twice, to Washington, to Boston, Baltimore, New York. She was entertained informally at the White House both times, once by President Bush at a lovely dinner in the family quarters – at the end of which he left by helicopter from the lawn for a Middle East peace conference in Spain – and once by Hillary Clinton at a lunch. She’s an outgoing woman. Sacie and I also traveled with her within Thailand, to the royal villas in the Northeast, in Chang Mai and in the South. We did three or four such trips. She enjoys those outings and they were fun to be a part of. There was always sumptuous food and spectacular table settingsand a very warm atmosphere. Sacie and I also got to know quite well Princess Sarandon, the eldest daughter, the Crown Princess. She’s a very impressive woman, a student of many things. She is serious about her role and she tries to perform that role to the best of her ability all the time. I have a great respect for her and so do the Thai people. My own meetings with the Crown Prince were also quite pleasant. Then the other daughter in Thailand, Princess Chulabhorn is interesting, quite energetic despite frail health.

One of the most memorable evenings that Sacie and I had in Thailand was a going away dinner offered by the Queen for us at her villa near Ayutthaya. We were told that we would be guided there by a police escort and that we should wait at the residence. The police escort would swing by and lead us to the villa.

We knew that it was going to be a late evening – both the King and the Queen are accustomed to late evenings, and undoubtedly

very late risings in the morning. We sat there in formal clothes until about 10:00 PM when the police escort rolled in and we were off to Ayutthaya. We reached the villa I suppose around 11:00 PM. We were entertained by a wonderful display of ceremonial dancing by the side of the river, while candlelit balloons rose up into the evening air. It was modestly spectacular, if I can put those two words together.

Mighty nice for an intimate dinner. There were 25 or 30 people invited. The ladies were all wearing black because the mother of the King had recently passed away. There were the usual lavish table decorations and a very lively atmosphere and it was, as the Queen’s gatherings generally tended to be, a genuinely enjoyable evening. We got home around 4:00 AM, as I recall. I think that was an unusual gesture on the Queen’s part and I appreciated it very much, as did Sacie. So, our experiences overall with the Thai royal family were quite positive. I have a good impression of them and of it as an institution.