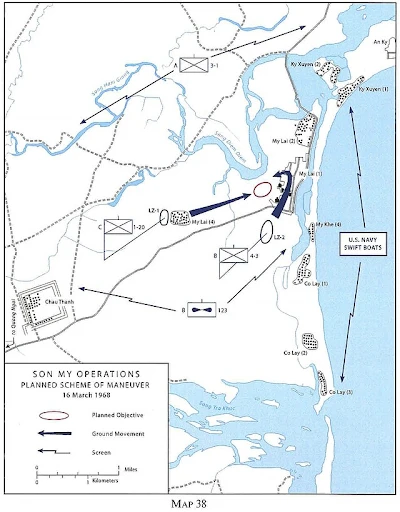

On March 16, 1968, in what was one of the most shocking incidents of the Vietnam War and in the history of the U.S. military, an estimated 500 Vietnamese villagers were killed by U.S. Army soldiers from Company C of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the 23rd (Americal) Infantry Division in the obscure village of My Lai in Quang Ngai province of South Vietnam. The massacre took place shortly after the January 30 Tet offensive in an area known to be a stronghold of the 48th Viet Cong Battalion, one of the most effective military divisions of the VC.

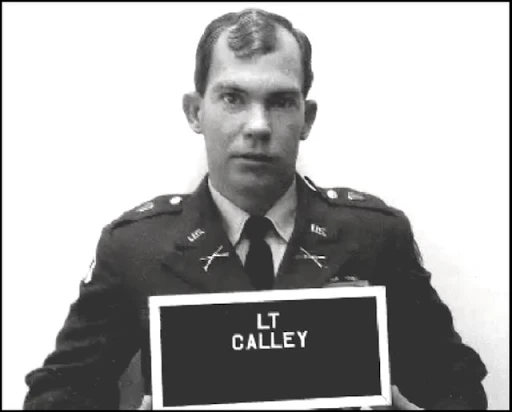

For nearly two years following the incident, investigations into the killings maintained a low profile while the American public, and even sections of the U.S. military and Foreign Service, remained largely unaware of the magnitude of the event. It was in mid November 1969, that Seymour Hersh, an independent investigative journalist, broke the story with his interview of Lt. William Calley Jr. who, in September of that year, had been charged with the murder of 109 Vietnamese civilians. A fresh investigation into both the cover-up and the war crimes committed was subsequently launched under the lead of Lieutenant General William R. Peers. Of all the officers charged during the course of the Peers Inquiry, only Lt. Calley was convicted. Initially sentenced to life in prison on March 29, 1971, Calley served only three and a half years under house arrest.

Carl Edward Dillery arrived in the province after the killings occurred as a Revolutionary Development Support Officer in March 1968. From June through December of the following year, he served as Province Senior Advisor in charge of both military and civilian aspects of operations on the ground. In the following excerpt, he describes his perception of the military tension in Quang Ngai around the time the killings occurred as well as his reaction and role when news of the massacre broke to the American public in late 1969. His account provides a subtle yet telling insight into the unspoken reluctance to report on the incident at the time. Dillery was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy starting in March 1994.

“The Whole Area Was Tense”

DILLERY: Quang Ngai is in I Corps which is the northernmost Corps of the four of Vietnam, and is the southern most province in that. It is two provinces below Da Nang. Quang Ngai is a large province with a population of about 600,000. The mountains came pretty close to the sea there. The Americal Division was the American presence. It had been one of the areas of heaviest Viet Cong presence, always, traditionally. A lot of North Vietnamese officials came from Quang Ngai, including the then Prime Minister, Pham Van Dong. It had quite a strong political tradition. There were five non-communist political parties in Quang Ngai, although some with membership of only four or five people.

When I arrived everything was pretty much besieged, it was right after Tet. The Province Senior Advisor’s house was a compound with several buildings and lots of rooms, and I stayed in one of those. It had shell holes in the gate from a mortar that landed during Tet. During Tet the fighting was only a block away. So when I arrived there was a strong feeling of tension, in fact I think I made a trip to one of the district offices and it was the first time they had driven out since Tet. [There was] a very, very, strong feeling of imminent danger.

Of the 600,000 inhabitants, 300,000 were refugees and one of our biggest jobs was taking care of them. My Lai occurred in that province before I got there.

Q: Had they started investigating that?

DILLERY: In a very desultory way the IG [Inspector General] and a couple of other army inquiries had come, but they never found anything until the story broke in December 1969. We didn’t even know what they were investigating. They were casting their questions in such a way that you didn’t know what they were talking about

Q: I was in Saigon later on. I came in early 1969 and there were sort of hints around, because I was dealing with the Inspector General too, of them looking for something big, but they didn’t say what.

DILLERY: We knew that the area around My Lai was the operating territory of the 48th Viet Cong Battalion, which was said to be one of the best Viet Cong military units in the whole country. That was real bad country out there. They were almost as formidable as the North Vietnamese army.

But the whole area was tense…

“We had something very serious on our hands here”

Q. What was your role during the My Lai investigation?

DILLERY: My own experience on My Lai was in mid-November, 1969…. I was in my office doing some routine work, and all of a sudden one of the staff came in and said, “There is somebody here from the OSI [Office of Special Investigations].” A Mr. Feher, [André Feher, the Chief Warrant Officer of the U.S. Army’s Criminal Investigation Division when the investigation into My Lai was turned over to it in August 1969] a very imposing person, came in and I thought, “Uh oh, they have caught me misappropriating funds.” I had a little slush fund of about a thousand dollars a month. You weren’t supposed to use it for labor but it turned out that one of the better things we did was repairing pot holes. So I used some for that. That was the only thing I could think of.

Anyway, Mr. Feher came in my office. He had a dossier about six inches thick which were the pictures of My Lai and reports about the incident. Looking at those pictures caused me to — it was like a light bulb going on — in about a tenth of a second to remember all these rumblings about operations in Quang Ngai in 1968…and I realized what had happened. I said, “I better go talk to the Province Chief about this.” So I took the file and went upstairs to see the Province Chief….

My District Chief, that is the district in which My Lai is, was in the building there for a meeting. I showed Col. Khien [the South Vietnamese Quang Ngai Province Chief] the pictures and said we had something very serious on our hands here. He called the District Chief out of the meeting and they began to talk. I didn’t speak Vietnamese but I could tell they were saying numbers of casualties bigger than anything I had seen in the dossier.

He said, “What should we do?”

I said, “Well, my first piece of advice is don’t try to cover this up because if you do, it is going to be worse as it is out now. I can tell you, in America you get into more trouble if you try to cover it up than if you just go with it and let people have access and find out what really happened, bad as it might have been.” He actually followed that policy for a while.

Then it turned out that the investigator wanted to interview the people who had been involved. He did that at my house. This was a little bit of a drawing room comedy because Henry Kamm [a New York Times reporter residing at the interviewee’s residence at the time] was there. I didn’t want Henry to be in the room with the investigator and the district chief, etc., so I had to move one group into the living room and another gently out — but it worked out okay.

Mr. Feher stayed for a couple of days. I hadn’t been in Quang Ngai when the incident occurred the time of the incident, but it turned out that a number of my close associates were implicated, at least in the reporting on the incident. Our Deputy Province Senior Advisor in 1968 was Lt. Colonel Bill Gwynn, a good friend and a superb officer. He was cited in the final reports on the incident in connection with the reporting on the incident. He was a good friend and [a] good guy. There were a lot of questions about the “cover-up” of the incident, [and I] must say that it was well enough covered up in 1968 and most of 1969 that I didn’t know anything about it. I did testify before the Peers Commission [chaired by General William Peers to investigate My Lai]…. I told them everything I knew, which wasn’t very much.

I had been in My Lai several times because the Province Chief took me out there a couple of times in 1969. I remember being in a meeting with the My Lai villagers and listening to him talk to the people. It wasn’t anything particularly different than being in any other village.

To put it in perspective, it happened just a couple of weeks after Tet and this particular company was brand new having just arrived in Vietnam. By the way, remember the Americal Division was made up overseas, it had never been formed in the U.S. and wasn’t a traditional one. So everybody always said it lacked a little bit of cohesiveness.

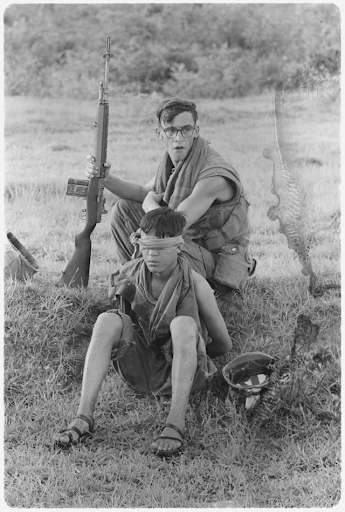

Calley was not very secure in his leadership. The Company had been told they were going to run into strong opposition in this village — from the 48th Local Force VC Battalion. They also had been told that there would be no civilians present since all would be at the market in another village — but they did not go to market that day. It looked like panic just took over. The Americans just started shooting and it went on from there.

Then there was no reporting at the Division level about the incident. Members of the Company and a photographer who accompanied them did try to raise the issue but inquiries did not get very far. As I mentioned earlier, there were several investigations — even Major Colin Powell conducted one — and there were questions afterwards, but the story didn’t break until late in 1969 when it became a major political issue in the United States….

The incident really was one of those things that led to the American public’s final negative reaction to the Vietnamese war. It was a very, very powerful public relations event. It was a real tragedy.