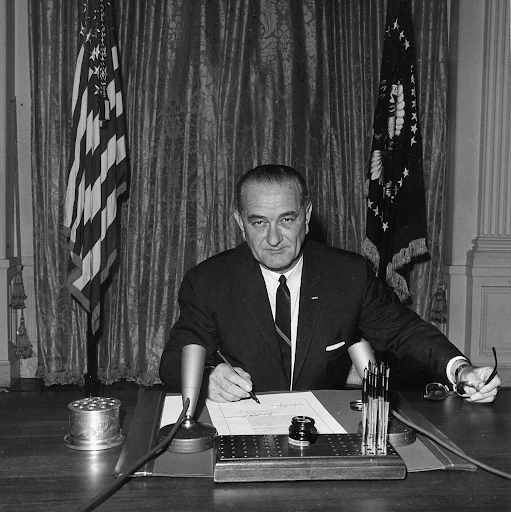

The Gulf of Tonkin attack on August 2, 1964 and another many believed to take place on August 4 led to an escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. The USS Maddox was patrolling the Gulf of Tonkin, situated between North Vietnam and China, collecting intelligence in international waters when it engaged three North Vietnamese naval boats. The Maddox initially believed it had been fired upon by three torpedoes, which all missed; it retaliated with over 280 3-inch and 5-inch shells, while jet fighter bombers strafed the torpedo boats. One U.S. aircraft was damaged and though one round hit the destroyer, there were no U.S. casualties. A second incident reportedly took place two days later but this appears to have involved false radar images and not actual torpedo boat attacks. As a result of these incidents, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted President Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to assist any Southeast Asian country whose government was considered to be jeopardized by “communist aggression.”

The resolution served as Johnson’s legal justification for deploying U.S. conventional forces and starting open warfare against North Vietnam. There has long been speculation that the Tonkin incidents were merely a pretext for LBJ and the military to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In 2005, an internal National Security Agency historical study was declassified, which concluded that “the Maddox fired three rounds to warn off the communist boats. This initial action was never reported by the Johnson administration, which insisted that the Vietnamese boats fired first.”

General Maxwell D. Taylor was Ambassador to South Vietnam from July 1964 until July 1965 and was interviewed by Ted Gittinger in September 1981. The Ambassador to South Vietnam from 1957-61, Elbridge Durbrow was in Paris at the time of the incident as a delegate to the NATO conference; he was interviewed by Gittinger in June 1981. Secretary of State Dean Rusk was appointed in 1961 and was a major player in President Johnson’s decisions concerning the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. Paige E. Mulhollan conducted this interview in July 1969. James F. Leonard, an employee of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), was in the Far Eastern Affairs bureau and was interviewed by Warren Unna in March 1993. Thomas L. Hughes was the Director of Intelligence and Research (INR) in the State Department and was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in July 1999. Go here to read other Moments on Vietnam.

“It seemed an obvious fact that attacks had taken place”

General Maxwell D. Taylor

TAYLOR: I would say that in Saigon we did not get an immediate interpretation from Washington as to what had happened. However, we intercepted the same information that Washington got and none of us questioned the fact that our ships had been attacked by North Vietnamese boats on both days. I can’t say we made an analytical study of the evidence, but it seemed an obvious fact that attacks had taken place. True, it had done no real damage to our ships, but nonetheless it was an act of defiance of the U.S. Navy to rush out into international waters and attack our ships, even if they didn’t do a good job of it.

I was surprised and disappointed we didn’t retaliate for the first attack and waited till the second. But I was happy that some retaliation took place, bearing in mind that it was really a symbolic kind of thing that didn’t do any great damage to the enemy and wasn’t expected to.

“We’re finally going to clean that place up”

Elbridge Durbrow

DURBROW: They started blowing up our barracks down there in the South and things of that kind. They’d done some of that when I was there, you know, they did two bombings when I was there. Fortunately, nobody was really badly hurt, but they could have been. They tried to do it subtly. I’m talking about the communists…Every once in a while they’d want to get a provocative thing going and they’d do it. It’s not done by some battery commander that got drunk that day and pulled the lanyard and shelled the land just as far as whatever it is.

I don’t know exactly what the motivation was, but they were up there in their territory, of course, in the Gulf of Tonkin, and they were getting pretty in close, I suppose, and they said, “Well, we’ve got to try to scare these guys off.” I don’t know. They’re not afraid of doing a thing like that and when they feel they’re not doing too well otherwise, why not try to shoot the works a bit?

By the way, I took my oldest son out to see the Verdun war battlefields out there, and we’d gone out for the weekend in Paris and were driving and I had the radio on and by golly, I heard about the Gulf of Tonkin. I cheered, “We’re finally going to clean that place up.”

“There was unanimity among Congressional leaders on the desirability of a resolution”

Dean Rusk

RUSK: They were on an independent intelligence-gathering mission in the Gulf of Tonkin. Of course, since it was high seas we expected to maintain our capability of being present in the Gulf of Tonkin, and we weren’t going to be driven off the high seas in the Gulf of Tonkin just because of a scrap going on in South Vietnam. But it is not true — and Secretary McNamara testified to this — that these vessels of ours were there covering or, in a sense, associated with some South Vietnamese coastal operation.

You see there had been a little guerilla war going along on the coast back and forth across the DMZ [de-militarized zone] between the North Vietnamese and the South Vietnamese. The North Vietnamese were using coastal waters for infiltrating men and arms into the South, and the South Vietnamese were retaliating. But the destroyers that were attacked in the Gulf of Tonkin were not there to give cover to operations of that sort.

When the Gulf of Tonkin came along and the President consulted with the leadership of the Congress, he discussed with them whether this was not the time now to go for a resolution putting the Congress behind the United States policy on Vietnam and making it clear to North Vietnam that we were serious about it. The Congressional leadership encouraged him to do so. There was practical unanimity among Congressional leaders on the desirability of a Congressional resolution, and so we had our hearings, and promptly the Congress passed the so-called Gulf of Tonkin Resolution with only two dissenting votes in the Senate.

Paragraph II of that resolution, which the historian will be able to see, of course, was not about the Gulf of Tonkin, but was about Southeast Asia, and it simply affirmed that the United States is prepared as the President determines to use whatever means are necessary including the use of armed force to assist the states covered by the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization in the defense of their liberty.

Now, there was no question at all at the time about the meaning of that resolution. (Read more from Dean Rusk’s interview.)

“You couldn’t say that it hadn’t happened, but you could not have said that it really did happen”

James F. Leonard

LEONARD: When I arrived I was curious about [the incident], because it to me had seemed like such an extraordinarily inexplicable and stupid action on the part of the North Vietnamese to have attacked our ships and brought down this escalation on themselves.

So I went back and looked at the classified material, and my conclusion from that was that you couldn’t say that it hadn’t happened, but also you sure could not and should not have said that it really did happen. Maybe there was other information that I never saw, but in fact I don’t think there was, and it’s all been researched and written up very thoroughly.

“Certain covert activities had been approved for this area”

Thomas L. Hughes

HUGHES: Sunday, August 2, occurred on another of those summer weekends when people were out of town. [Secretary of Defense, Robert] McNamara was climbing mountains in Wyoming. The Bundys [National Security Advisor McGeorge and his brother William, CIA officer and later Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs at the State Department] were up in Massachusetts. I happened to be here [Washington DC], was awakened early in the morning, and summoned to [Secretary of State Dean] Rusk’s house for breakfast.

There I found myself in the company of Rusk, [Under Secretary of State George] Ball, Cy Vance (McNamara’s deputy), General Wheeler, the newly appointed Chairman of the JCS [Joint Chiefs of Staff], and a couple of men from the CIA and the Navy. We were briefed about an attack on the USS Maddox. The evidence pointed clearly to North Vietnamese PT [patrol torpedo] boats as the culprits. The Navy had sent the Maddox into the Gulf of Tonkin to show the flag and perhaps to be on the scene in case there was any intelligence to be gleaned from radar activity along the shore.

While Virginia Rusk cooked pancakes and served us breakfast, we sat on the floor looking at maps of the Gulf of Tonkin, noting the proximity of islands, speculating about 3-mile versus 10-mile off-shore claims, and guessing where our destroyer might have been. We were also aware that certain covert activities had been approved for this area, the so-called 34A operations. No one knew whether the captain of the Maddox knew about them, or whether the South Vietnamese involved in the 34A ops knew about the Maddox. The Pentagon seemed doubtful about both issues. The scene was reminiscent of the Versailles Peace Conference with Lloyd George and Clemenceau struggling to locate Trieste on their map of the Adriatic. Anyway after we brainstormed this for a couple of hours our small group first went off to our respective offices and then to the White House to brief Johnson.

The missing leadership was back in town by August 4 in time to handle the so-called second attack at the Gulf of Tonkin. McNamara with his usual decisiveness took charge of verifying the authenticity of the whole event, after doubts had been raised and LBJ briefed about them. Johnson demanded certainty before acting, and the Pentagon rose to the occasion by resolving doubts in favor of certainty.

Johnson arranged for McNamara to brief Capital Hill and without further ado, McNamara testified with assuredness about the second attack, misleading the Congress, and propelling more or less everybody into supporting the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. Not that Johnson didn’t rather welcome the opportunity. Assistant Secretary Bill Bundy had drafted the resolution and had it on the shelf for just such an occasion. At the time, the resolution’s supporters, including [Senator William] Fulbright the floor manager, were chiefly worried about [Senator Barry] Goldwater who was now the Republican nominee for president and eager to denounce Johnson for inaction.

The conventional wisdom now discounts any second attack. The North Vietnamese at the time and since have denied a second attack. Apparently readers of the intercepts at the Pentagon mixed up the times and dates on the telegrams. Those that they thought were referring to August 4 really referred to August 2. The certainty contained in the McNamara testimony was not corrected after contrary conclusions were reached.