In the late 1960’s, the United States had become polarized by the Vietnam War, as even many defenders were beginning to question the goals and tactics of the military. One such person was William Watts, who at the time had been promoted to the position of White House Staff Secretary for the National Security Council under President Richard Nixon in 1969. As such, he worked closely with Henry Kissinger, who at the time was National Security Advisor, as well as prominent people from the Nixon White House, such as H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. Bureaucratic tensions were often high and interpersonal skills were often lacking, which not surprisingly led to bitter infighting and nasty confrontations over policy. U.S. policies on Vietnam and the planning over the invasion of Cambodia, which took place from April-July 1970 were strongly opposed by Watts, which left him an outsider. Watts resigned from the NSC in 1970 after a fiery exchange with Alexander Haig, then Nixon’s White House Chief of Staff.

In an interview with Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning in August 1995, Watts recalls his experiences working personally with Kissinger and Nixon, the nasty atmosphere that permeated the NSC at the time, and his heated resignation as Staff Secretary after questioning the morality of the very policies he was helping to implement.

“Kissinger and Nixon had very exceptional brains. They were also amoral in the very basic sense of the word”

WATTS: I was what used to be the Executive Secretary. What happened was when Kissinger took over, he did not want to and Nixon did not want to have…the Executive Secretary of the National Security Council…position approved by Congress. The National Security Advisor slot is not approved by Congress; I personally think it should be….

So, they gave my job a different title, Staff Secretary, and I didn’t have to be confirmed by the Senate. I was basically in charge of running the thing, making it work. I did not have a specific line responsibility for any single policy. But on the other hand, the way that Henry worked, meant that I got involved with things across the board.

For example, the China opening, the staff member responsible for China was not brought in at the outset on much of what was going on. We had a third-country intermediary who was going back and forth between Washington and Beijing with a one-time pad. We were dealing directly: the link was between Kissinger and [Premier] Zhou En-lai. This guy was delivering messages back and forth, unknown to the NSC man and Bill Rogers, the Secretary of State. This was the way that Kissinger and Nixon worked.

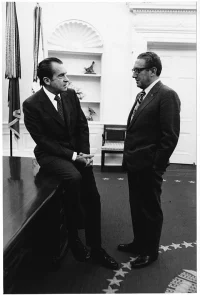

A combination of factors: One, Kissinger at the beginning was extremely nervous. He came in as an outsider to the Nixon operation. Obviously he had been working for [Nelson] Rockefeller for years, and he had let it be known that he didn’t think much of Richard Nixon. [At left, White House Chief of Staff H. R.] Haldeman and [Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs John] Ehrlichman cordially despised him, and he cordially despised them. They were constantly making all kinds of disparaging remarks about him.

I remember once going up in the elevator in the West wing, and we were going to see Nixon. When we got into the elevator, Haldeman and Ehrlichman were there. It was a small elevator, you could only get four people in it. There had been an article in The [Washington] Post saying that Kissinger had been seen the night before at some watering spot in Georgetown with some attractive woman and they both said, “Gee, I thought you only took out boys.” This kind of stuff. It was rather sleazy.

There was this backbiting that you just can’t believe. The saddest part of it to me was that you had two men who had superior intellects. Kissinger and Nixon had very exceptional brains. They were also, in my view, amoral in the very basic sense of the word. Right and wrong was not part of their calculus, it was win and lose. They had in their natures, which I felt was so debilitating in working there, this combination of secrecy and paranoia. If you had people with comparable intellect and nobler instincts it could have been one of the great combinations in the history of the human race in terms of ability to achieve.

When I came down [to the NSC], part of it was because Larry [Eagleburger] had moved off to Brussels. [Alexander] Haig came a little before I did, he was a colonel. I came to view him as driven and narrow. The “I am in charge here” statement, after the Reagan assassination attempt, was typical of that driven nature. Tony Lake had a front office staff assignment role, and became very involved in the secret Vietnam negotiations. He became almost like a son to Kissinger. It was a very close relationship….

Q: What was the feeling among you all…those of you with a Foreign Service background…about the Nixon and Kissinger approach to Vietnam?

WATTS: That was a very mixed bunch of people we had there at the time…On Vietnam, I don’t know how a lot of the others like [Kissinger protégé Helmut] Sonnenfeldt felt. It was very much structured along the lines of the State Department by bureau. The people who were most directly involved – [State Department Asia hand John] Holdridge, Grant and the CIA guy — were kept out of a lot of stuff. For example, when Nixon decided to give his famous Vietnamization speech in November 1969, Tony Lake, Roger Morris [who resigned in 1970 and later became known for his political writing] , and I were given the first-draft task. The Vietnam people weren’t even brought in on it. We drafted a speech which was getting us out of Vietnam in somewhere between six and eight months. We wrote a very dovish speech, which didn’t get very far. The final speech was basically written, as I understood it, by [Nixon speechwriter and later renowned columnist] Bill Safire and people like Pat Buchanan and Ray Price.

It is interesting, people didn’t talk across their policy boundaries very much. At least I didn’t have that sense. Staff meetings were kind of pro forma, and they eventually pretty much stopped. Like the NSC meetings that gradually got less and less frequent, and became less and less meaningful. Everything tended to get handled more and more by direct action: NSC staff would prepare the memo, Kissinger would take it to Nixon, he would approve, and we would act, without going through the standard NSC channels….

I think it would be fair to say that general foreign policy the thinking of the NSC staff as a whole was substantially more liberal vs. conservative, multilateral vs bilateral/unilateral, than that of the views of Nixon and Kissinger. Basically you would have thought that this was a Democratic administration in terms of a lot of people on the NSC staff.

“The strategist of these two was not Kissinger, it was Nixon. Kissinger is the tactician”

Q: Did you find that Kissinger was sort of hung up in a political litmus test on things he sent up to Nixon or was he giving his best shot as where things should go rather than what would gather more Republicans together?

WATTS: I think that he and Nixon over a period of time came to feel that their views were in sync. That is a very, very difficult question to answer because that is not something I discussed with him. But, I would say that I think his way of dealing and what went forward, by and large would be something that because he knew what Nixon was after and he agreed with, was going to work in that direction.

You know, it is very interesting. [Famed journalist] Scotty Reston had an interview with Kissinger, which I must track down because it is one of the most revealing interviews of his. At one point, Kissinger was then Secretary of State by that time, Reston asked him, “Henry, you are credited with having a grand world view and a global strategist. What is your view?”

And then it said [Kissinger chuckling], “If you want to find my world view you will have to check with my speech writers.” I thought when I read that, this was after I had left, that it was so revealing: the strategist of these two was not Kissinger, it was Nixon. Kissinger is the tactician. And this is one of the reasons that they worked together so well. I think Nixon really did have a real world view and that Kissinger understood this and was the guy who could do all the skulduggery to get things moving in that direction….

Q: Did you find in the various areas there one has the feeling that certainly until late, Kissinger had no interest in Africa or Latin America?

WATTS: The period I was there, through the middle of 1970, the overriding focus was on four things: The Soviet Union, SALT [Strategic Arms Limitation] Talks, and very secret stuff going on in terms of Vietnam, and very secret stuff going on concerning China. But publicly the emphasis that was being taken was the Soviet Union and the SALT Talks.

You have to remember that this is the period leading up to the riots in Washington, the march on the White House where people were walking around with candles. The night of that march, Tony, Roger and I were in the White House basement drafting this Vietnamization speech for Nixon.

At that time, I was still smoking and I went up to take a break and walked down to the southwest gate and people were walking around out there and there was my wife and three daughters with candles. They didn’t see me. You talk about emotion. I am on the inside, the enemy, and there are your own wife and children outside marching….

Q: In the process, were you all making decisions and setting the parameters first?

WATTS: This probably happens with every administration, at the beginning we had what were called NSSMs, National Security Study Memorandums. That would go out from Kissinger saying the President wants to dah-dah-dah, and that would go to wherever it should go to in the bureaucracy. Papers would come back. There was a committee, the Under Secretaries Committee, which was the highest committee under the NSC, which would meet to review all of the different stuff that had come in from the various departments, and a conglomerate paper was put together and ultimately wind up as being the NSC system paper on the subject. But, as I say, that tended to be very long and it had to have a cover which was written entirely in the White House. That was where we took over, the NSC staff took over. Now, sometimes, in some cases, it never went through that whole process. We just did it.

As the relationship between Kissinger and Nixon grew…it took quite a while to get to this, well on after my stay, about a year…Kissinger would sign off for Nixon on some stuff. The one thing you never know on this, and I don’t know how it works now, Kissinger would go to see Nixon every day. I used to have to come in about 5:30 or so to go over the night’s take to put together the points for his meeting with the President at 8:30 or whenever it was. We would have to figure out what was the really critical stuff that has come in and he would want to discuss with the President.

And then, of course there would be other things that were pending issues, etc. Those meetings were alone. What was decided in those, it was hard to tell. But I think one of the things that clearly would happened is Henry would get essentially a go-ahead in certain areas. When he came back he would then be willing to sign off on something having discussed it with Nixon….

“I was getting increasingly frustrated personally by my job….I was very, very against what we were doing in Vietnam”

I was getting increasingly frustrated personally by my job. What was happening was that Al Haig was moving himself up in the hierarchy and he had gotten by this time another star or two which must have been among the fastest promotions in the history of the military. The guy was a tough infighter.

As I said I was getting frustrated by the realization I was being pushed aside, and the fact that I had just really become very, very against what we were doing in Vietnam. That big march [in October 1969] that they had around the White House, there was a double line of buses all the way around. There was only one way you could get in, and that was a small opening between two of the buses.

I left to go out and join with these protesters out there, sitting with those kids all smoking pot and Dwight Chapin, Nixon’s appointment secretary, comes through taking pictures.

He looks down at me and says, “What are you doing here?”

I said, “I’m with them.”

He said, “What?” And then these kids say, “Who are you?”

I said, “I’m on Nixon’s National Security Staff,” and they are all cheering that I am out there with them.

But this had been building up going back to that November speech and the Cambodian thing was the following April. I found myself working for an administration, and with a particular group of people who I was coming to respect less and less, i.e. Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, Al Haig, and to a lesser degree, Haldeman. Ehrlichman I actually quite liked. He was really quite a nice guy. Haldeman was a real ice man in there.

I was finding myself increasingly in this position of being in the middle of something I didn’t want to be in the middle of. By this time Tony [Lake], Roger [Morris] and I had really kind of gotten to be quite close and spent a lot of time together talking things over. We were all sort of moving in the direction of leaving.

What happened in my case as we went into that final week of going into Cambodia, suddenly Henry decided to use me in terms of handling and coordinating a lot of the most highly sensitive [issues]…There was a special Khmer slug [tag for cables] that was put on anything to do with the operation, and that came only to me and a few others.

Then, we went through this famous Friday night meeting, the so-called “bleeding hearts” — Henry’s term for us — meeting, when he called Tony and Roger, Bob Osgood, who was the head of the long-term policy office in the NSC which had no role, Larry Lynn, who ran the systems operation, and myself together.

Henry said, “We are going into Cambodia, the decision has been made, using fixed-wing aircraft.” This is something I will always regret that I didn’t say, “Yes, but it is also ground troops.” I didn’t say it, I wish I had. I know that Tony knew it, but I don’t know who else knew that. This thing was really handled tightly.

At one point he asked what we thought and I did said, “Henry, one thing is that we are going to go into Parrots Beak and Fish Hook [Vietnamese sanctuaries on the Vietnam-Cambodian border], we are going to flush them out of there and they are going to run all the way to Phnom Penh, and that is the end of Cambodia.”

That was Friday night. He called me Saturday night before I left and said, “We are meeting tomorrow at 4:30 Sunday afternoon and the President is going to name you as the staff coordinator for this operation.” I had written a memorandum earlier to Nixon, through Kissinger, about the so-called October Option, “Operation Duck Hook,” which was going to be a massive bombing of Haiphong and Hanoi, opposing it.

In the memo I said that if you go ahead with this, my prediction was that we were going to have massive rioting around the country. That the National Guard was going to be called out and that some students were going to be killed somewhere. My last sentence in that memo was saying that “You will have to be prepared to deal as brutally with domestic dissent as you are with the Vietnamese communists.” Again, it was just read with RN and HK [Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger] initialed on it when it came back. No comment.

So, I just sent it back saying, “Henry this is it, I said it all right there.” The next thing I know these guys say I am the staff coordinator.

“I just came up out of my chair swinging, I was so damn mad”

So, I went home Saturday night and sat up a good bit of the night and went off that Sunday to the office to get ready for this meeting. I don’t think when I left the house I was sure what I was going to do. I went through the day preparing for the meeting and finally I said to myself that I won’t do it.

So, at 4:00 I went to see Henry. When I came down here I had written a letter, because I wanted it in writing, saying that I was coming to work for Henry, but that my loyalties go in the following order: 1) to my country and the American people, 2) to you, and 3) Richard Nixon. I am surprised after that letter that he gave me the job.

I said to Henry, “You remember what I said in my letter when I came here? Well, you have just called my bluff and my loyalties are to the American people and I’m refusing the assignment, I am leaving.”

And then Kissinger said something that I will never forget. He said, “Your views represent the cowardice of the Eastern Establishment.”

I just came up out of my chair swinging, I was so damn mad, and missed him. He ran behind his desk and said, “I am only kidding.”

I said, “Well, you don’t kid about something like this,” and just stormed out of the room. The buzzer in Haig’s office was ringing, and he goes in. I went straight to go see Winston Lord, who had moved in there as sort of an assistant. I told Winston what had just happened and said, “I’m leaving and I’m sure he is going to appoint you to replace me, so you had better be ready because he is going to call you in any minute.”

Suddenly Haig came flying out of Henry’s office and came back into the situation room. He said, “What the hell did you say to Henry? He is furious. He’s throwing books around the room and screaming and yelling.” So I told him that he said I was to be the staff coordinator and I wouldn’t do it.

“He said, ‘You have had an order from your Commander-in-Chief and you can’t refuse.’ I looked at him and said, ‘Fuck you, Al, I just have and I am resigning’”

At that point Haig then looked at me and used a line that not long afterwards he used with [Deputy Attorney General] Bill Ruckelshaus at the time of the “Saturday night massacre” [when Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox was dismissed by Nixon and Ruckelshaus and Attorney General Elliot Richardson resigned in protest in October 1973]. He said, “You have had an order from your Commander-in-Chief and you can’t refuse.”

I looked at him and said, “Fuck you, Al, I just have and I am resigning.”

This all appeared in “The Final Days,” Woodward and Bernstein’s book and in Sy Hersch’s book, “Price of Power.” My dear mother, bless her soul, later was reading “The Final Days,” and came across all of this in the book and she called me up and said, “Willy, did you really try to hit Mr. Kissinger?”

I said, “I sure did.”

“And did you really say that terrible thing to General Haig?”

And I said, “Yeah, Ma, I am afraid I did.”

And then she said, in a sweet plaintive voice, “Does it have to appear in print?”

Anyway, I left. I got home and walked up the walk to my house and my wife opened the door. She didn’t know for sure what I was going to do when I left that morning, and said, “You resigned, didn’t you?”

I said, “How do you know?”

She said, “You are smiling for the first time that I can remember.”

It was really interesting. So, that was the end of my government career….

I will have to say John Holdridge came to me saying, “You have to stand behind the President, he is putting his political career on the line, we must rally behind him.”

I said, “No way, I am out of here.” I think John was genuinely shocked when I resigned. John is a military graduate and is used to a command structure that gives and takes orders well.

Q: A couple things on this. There is an aftermath. So often when one resigns one is picked up by whatever amounts to the opposition and used in such a way that one finds uncomfortable. Did you find this happened?

WATTS: No. I was approached by several newspapers and individual journalists that offered some pretty handsome sums of money for a big interview, but I refused all of that. Actually, I got out of the country. My ex-wife and I had a place in the Bahamas and we took off and went down there. My decision at the time, to me, was very simple.

In retrospect, and I have talked about this with Roger Morris, we both agree that we made a mistake, we should have gone public by calling a press conference and announcing our resignation and why. And perhaps even said that there was going to be an invasion of Cambodia, although we could have gone to jail for that and also could be threatening a lot of lives, but at least after the fact to come out and say something.