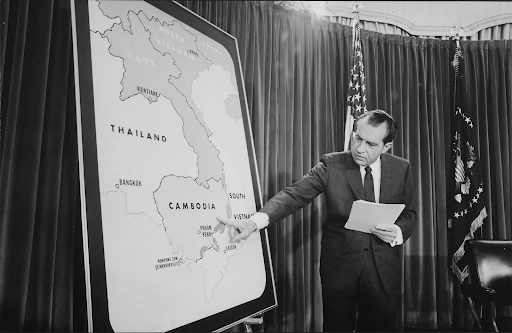

When President Richard Nixon took office in 1969, he and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger vowed to find a way to end U.S. involvement in Viet Nam quickly and honorably without appearing to cave in to communist pressure. The U.S. launched a secret air campaign, thirteen major military operations, against North Vietnamese bases in Cambodia. Cambodia’s neutrality and military weakness had made its territory a safe zone where North Vietnamese troops established bases for operations over the border.

President Richard Nixon gave formal authorization to commit U.S. ground troops, fighting alongside South Vietnamese units, against North Vietnamese troop sanctuaries in Cambodia on April 28,1970. The incursion was possible because of a change in the Cambodian government in which Prince Norodom Sihanouk was replaced by pro-U.S. General Lon Nol. News of the military action in Cambodia ignited massive antiwar demonstrations in the U.S., in part because the determination to invade was made secretly.

Meanwhile, the U.S. embassy in Phnom Penh, which had closed in 1964, was in the process of reopening. The fact that only a small circle of people in Washington knew what the Nixon administration was planning to do in Cambodia, including the April 1970 incursion, complicated the work of U.S. diplomats there.

L. Micheal Rives, Chargé d’ Affaires at the U.S. Embassy Phnom Penh from 1969-1970, was in Cambodia at the launch of the incursion. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in July 1995. Marshall Green served as Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs (1969-1973) and spoke with Kennedy in December 1988.

To read more about the Viet Nam war, Cambodia, Henry Kissinger or military operations, please follow the links.

“My general job would be to reestablish relations, and when things got better, we’d send an ambassador”

L. Michael Rives, Chargé d’ Affaires, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 1969-1970

[T]here was no assignment for me, so I took my vacation… and I was sitting on the beach when I got a frantic call from Washington. It was Tom Corcoran, who was then the Laos-Cambodian desk officer, Country Director, and he asked me if I would be interested in being Chargé, reopening the Embassy in Phnom Penh (seen at left in 1965.)

The Department was not very enthusiastic about this idea… it was Tom’s suggestion. They wanted somebody more junior than I was. But he persuaded them, and I came down to Washington, and it was agreed that I would reopen the Embassy in Phnom Penh. For various reasons they [the embassy] had been closed down five years when I went there.

When I was called in and asked to go out there, there were two people who were very interested. One was, of course, Marshall Green, the Assistant Secretary, and the other was Senator Mike Mansfield (D-Montana.) Before I went to Cambodia, I was sent to see Senator Mansfield. It was understood by Sihanouk [Ruler of Cambodia], and Senator Mike Mansfield insisted, that there would be an Embassy opened at the Chargé level, and that there would be no CIA. If there was the CIA, the Embassy would be closed…

My general job would be to reestablish relations, and when things got better, we’d send an ambassador. So I went out there. Eldon Erickson had been out there already. He was waiting for me. He’d been out looking for buildings, that kind of administrative thing.

So I moved into the local hotel at that time, and opened our Embassy there in one of the cottages. I had been there about two or three weeks or something when Senator Mansfield came on a visit (seen at right.) Meanwhile, I had called on the Foreign Minister, of course.

Prince Sihanouk gave a luncheon for myself and Senator Mansfield, just the three of us. We had a very pleasant lunch, and at the end, Senator Mansfield was really very kind. He got up and gave a little speech and told Sihanouk that he was hoping for better relations.

He pointed out the fact that Sihanouk and I were of almost an identical age, and that he’d known me for years, and etcetera like that, and he hoped we’d get to be good friends. So that was a wonderful introduction to Sihanouk.

From then on, things were pretty normal. You know, I had established some contacts and did my political reporting. I was completely alone there for a while, except for a secretary and then I finally acquired a little staff. We found a building on the riverfront and moved in. We used the servants quarters in the back for office space.

We had no furniture, although we were told we were going to get some. The press became interested. Once in a while they’d come visit.

“When you went to one of Sihanouk’s parties, you were prepared to spend the night”

But the thing that really got things going as far as the Cambodian situation went, was the secret bombing of Cambodia, of which I was completely unaware.

At night Phnom Penh used to shake, literally. You could hear it. But I assumed it was on the border. And then one day one of our air attacks destroyed a Cambodian outpost up north, and that really did cause quite a furor. It was all publicized, so it was known.

That evening, Sihanouk (seen left) was giving a large party at his house. When you went to one of Sihanouk’s parties, you were prepared to spend the night, because he not only had a good party, but he would join the orchestra. He was a very good musician, played three or four instruments, and of course, nobody could leave until he gave the signal. So as long as he was happy playing, we all had to stay there.

That evening I went there prepared for the worst. The Chinese were there, and the Russians were there, and the French were there, and everybody else. They were all looking to see what his reaction would be to me.

At first, I wondered whether I should go, but I thought, “What the heck, I’d better go.”

So I went, and this was typical of Sihanouk: he played it straight. He met me, and everything was wise and well, and I danced with Princess Monique [Norodom Monineath] and all that kind of stuff. All to the disappointment of all the other foreign guests. I think they expected him to snub me, you know, raise hell because of what had happened — which he’d done already, privately.

“We’d sit there in the blazing sun, and then he’d insult us”

When I was there, we used to go out in the country to open a rice mill or new plantation or something like that, from time to time. It became really rather a joke between me and the French Ambassador and the British to see who would be insulted that day, because we all took our turns. Every time he had an opportunity…

He’d attack the United States one day, and then the next day he’d attack the Russians, and then he’d attack the French, and then he’d attack the Chinese, and then he’d let the British have it. So we all took our turn. We all braced each day when we went in to see who got criticized. But it was that way. It was deliberately done…

He’d attack us, and he’d criticize the attitude of the United States for what we were doing in Vietnam, and he’d criticize the French for not helping them enough, and the Russians for being brutes, or something like that…

He’d make a public speech during the opening of a rice mill or something. He’d drag in one of us at each occasion. We would all be sitting there waiting, because we were all ordered to be there, you know. We’d all ride in convoys, and we’d sit there in the blazing sun, and then he’d insult us! But it was a balancing act, and he did it very deliberately…

And then, of course, the other thing I was supposed to do, which I never succeeded in doing, was to try to get him to accept our intelligence information about what the Viet Minh and the Viet Cong were doing. I gave that information to him and to the Foreign Minister regularly, but he would never acknowledge it, and he never did anything that showed he was taking action against them.

He was not playing the Viet Cong game, but I think he realized he couldn’t do anything about it.

“I said, ‘There are no American troops around here,’ at which point an American helicopter started circling around Phnom Penh”

President Nixon decided there would be a limited attack into Cambodia, supposedly to capture the Viet Cong headquarters, which was never found and apparently didn’t exist, but apparently we thought that it was there.

It was a limited incursion, supposed only to last three or five days, something like that… The second objective, of course, was to include the newly trained Vietnamese troops to see how well they did. (They apparently did very well.)

The result of the incursion was two-fold. One, it failed in its objective of finding and destroying [the Viet Cong] headquarters, but it was very successful as an attack. What it did do was to push the Vietnamese back.

Now, the Vietnamese had known this was going to happen a couple of days before, because the French general told me when the incursion started, “the Americans had better move fast, because the Vietnamese are pulling back from the front towards Phnom Penh, and they’re not going to succeed very well unless they do something in a hurry.”

I informed Washington about this. Something strange was going on, I knew. The President kept his word. The incursion lasted, what, three days, I think it was, and then they pulled out.

As I say, I hadn’t been informed, and nobody was supposed to come towards Phnom Penh, and of course the place by then was swarming with reporters, who came to see me.

Of course, I was perfectly innocent about the whole thing, and I said, “There are no American troops around here.” At which point, an American helicopter started circling around Phnom Penh.

“It was at that stage the views of State and the White House began to diverge”

Marshall Green, Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, 1969-1973

At that stage — that is in late 1969 and early 1970 — the White House and State seemed to be agreed on doing all we could to uphold Cambodia’s neutrality. That seemed to be the only effective way of preserving Cambodia’s territorial integrity… The French were seeking to promote support for Cambodian neutrality with China through the efforts of their Ambassador in Peking.

But their effort got no positive results because of Hanoi’s strong opposition conveyed to Moscow and Peking. Anyway, it was all a futile exercise because of what was about to happen…

Sihanouk left Cambodia in late January 1970 for France, where he planned to spend a couple of months on the Riviera for health reasons. He did this often, but on this occasion he may have had in mind to extend his absence from Cambodia in order to visit Moscow and Peking with regard to North Vietnam’s operations in Cambodia. Anyway, Sihanouk departed for Paris, leaving the government in the hands of General Lon Nol and his Foreign Minister Sirik Matak.

During Sihanouk’s absence in France, there were growing student-led demonstrations in Phnom Penh against corruption involving the Sihanouk government in general, prominently including Princess Monique (Norodom Monineath, seen right), Sihanouk’s wife, who was running gambling casinos.

There was also resentment against Sihanouk’s inability to keep the Vietnamese out of Cambodia. Overall, it was clear that the better-educated Cambodians were tired of Sihanouk’s rule and had no trouble in gaining the support of students and the military. The peasantry was not involved, remaining loyal to Sihanouk.

Starting with demonstrations in Svay Rieng Province, followed by the sacking of the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong Embassies in Phnom Penh by thousands of youth (probably with Lon Nol’s connivance), Sihanouk angrily left France for Moscow on March 13.

It was at that stage the views of State and the White House began to diverge. The deposing of Sihanouk by unanimous vote of the National Assembly on March 18 marked the beginning of a new era in Cambodia, which the State Department saw as fraught with dangers but which the White House saw in terms of opportunities to build up Lon Nol and strengthen the FANK (Cambodian army).

President Nixon asked me to draft several personal Nixon-to-Lon Nol telegrams containing rather extravagant expressions of friendship and support. I was concerned that Lon Nol would read into these messages a degree of U.S. military support and commitment that exceeded what our government could deliver (given Congressional attitudes in particular).

“I warned against active U.S. intervention in Cambodia”

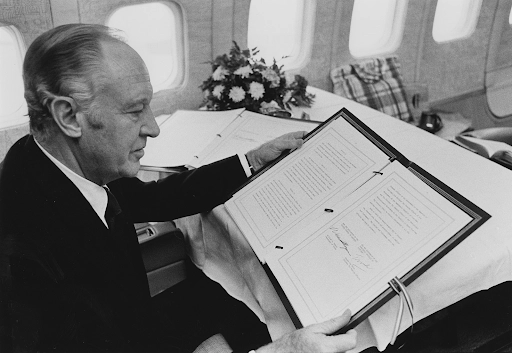

A solution based on Sihanouk’s restoration was by then out of the question, at least for an indefinite time. This prompted me to prepare a recommendation in the form of a four-page memorandum reviewed and approved by my colleagues in State, including INR. With [Secretary of State William P.] Rogers’ (seen right) approval, it was sent to Al Haig, Kissinger’s deputy, since he was emerging as the key man in the White House on Cambodian policy.

The memo analyzed Peking’s and Hanoi’s conflicting interests and motivations with regard to Cambodia. Peking, for example, probably saw its interests served by an Indochina composed of separate “independent” states, whereas Hanoi seemed bent on making all of Indochina subservient to Hanoi.

As to U.S. policy, I warned against active U.S. intervention in Cambodia since that would inevitably connote a continuing U.S. responsibility to sustain its government, and that could not be achieved without a sustained large deployment of U.S. forces there — an eventuality which was politically impossible given the mood of our Congress and people.

[My memo said that] under the circumstances, our policy should be one of “waiting on events, saying little except acknowledging our broad support for Cambodia’s neutrality.” (France was still hoping to entice Sihanouk back to France and thence to have him return to Cambodia possibly with Soviet and even Chinese connivance.)

[The memo noted that] as to South Vietnamese cross-border operations against communist sanctuaries in Cambodia, that should be encouraged, but without any U.S. involvement, for we must do all possible to support the case for Cambodia’s neutrality and territorial integrity.

My memo was ignored or rejected by the White House. Haig, in fact, urged U.S. intervention and the President, and then Kissinger – somewhat reluctantly – agreed.

“If that’s so, then our Vietnamization program was a clear failure”

At about this time (early April 1970), differences arose within the State Department over the issue of U.S. military weapons assistance to Cambodia. All of us were opposed to U.S. force involvement, but Bill Sullivan (my deputy who was also chairman of the Interagency Task Force on Vietnam) favored sizeable U.S. arms assistance to Cambodia, insisting that all such assistance had to be overt.

Concealment was both impossible and politically unacceptable… I felt that rather than trying to arm and equip the Cambodians (something Congress strongly opposed), we should encourage the South Vietnamese to conduct raids against these [communist] sanctuaries in Cambodia.

However, Ambassador [Ellsworth] Bunker and [U.S. Army] General Creighton Abrams (seen left) evidently sided with the White House in believing that the South Vietnamese were unable to conduct successful raids against these sanctuaries without strong U.S. support.

My reaction to that thesis was: well, if that’s so, then our Vietnamization program was a clear failure — and we will never be able to get out of the Vietnam quagmire.

It was at that point, around April 20, 1970, that Lon Nol sent Nixon a long telegraphic request for weapons to defend Cambodia. The request far exceeded levels which even the White House felt our Congress would support.

So, at that point, Nixon evidently came up with a stratagem to gain strong Congressional approval for the secret plan he had evidently been drawing up with the approval of Bunker and Abrams (but completely behind the back of the State Department, including Rogers.)

He sent Rogers on April 27 to the Hill to gain Senate support for a strong South Vietnamese attack against the sanctuary areas in Cambodia. I accompanied Rogers.

Rogers told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that we had just received a request from Lon Nol for U.S. military equipment. Senator Fulbright asked for specifics about what kinds of weapons, and in what quantities.

At Rogers’ request, I then read out the list of specific requests. Fulbright exploded: “Why, that must amount to over half a billion dollars!”

Then Rogers said: “You tell them, Marshall, what we figure it all adds up to.” I told the Committee that it amounted to $1.4 billion. This shock treatment had its calculated effect.

Said Senator [Frank] Church (D-Idaho) (seen left), with the nodding assent of his colleagues: “I have no objection to South Vietnamese involvement in Cambodia. Cross-border operations are okay. Here, in fact, is a good place to test the effectiveness of Vietnamization.”

Said Senator [John Sherman] Cooper (R-Kentucky): “The President now has support for Vietnamization. Let’s not destroy that.”

Now, what Rogers didn’t tell the Senators (evidently because Rogers didn’t know) was that the White House was not just seeking Congressional endorsement for South Vietnamese attacks against the sanctuaries, but also to have these attacks supported by U.S. ground forces.

All this was, of course, to lower Rogers’ standing with Congress: either he knew and was artfully deceptive, or he didn’t know and was without influence.

“I gathered he had just given his reluctant consent to this ill-advised operation”

I learned of it the day before the incursion was launched on April 30… I was astounded when Kissinger mentioned the President’s decision to commit U.S. ground forces. When I registered my objections as State representative at that meeting, Kissinger said the operation was already approved by the President.

I could see what a spot the decision put Rogers in with the SFRC [Senate Foreign Relations Committee.] Rogers was subdued when I called him about the WASAG [Washington Special Action Group] meeting. I gathered he had just given his reluctant consent to this ill-advised operation.

I was with Rogers in his hideaway office on the seventh floor of the State Department late in the evening of April 30, listening to Nixon’s announcement over TV of his rationale for ordering the incursion, including U.S. ground forces.

As Nixon concluded his maudlin remarks about the U.S. otherwise appearing as a “pitiful, helpless giant,” Rogers snapped off the TV set, muttering, “The kids are going to retch.” He clearly foresaw how the speech was going to inflame the campuses. That was several days before Kent State…

As usual, in such situations, we in State, responsive to White House direction, immediately set about the task of giving diplomatic, VOA [Voice of America] and other PR support to the President’s decision (including explanations to Lon Nol why he was not consulted on the incursion).

As a May 9 WASAG meeting in the White House basement concluded, Nixon wandered in and took an empty seat next to mine at HAK’s [Henry Kissinger’s] conference table. He turned to me and said something to the effect that, whereas I had opposed the incursion, he appreciated the fact that I loyally carried out the President’s decision.

All during May, I was the leading State Department briefer on events leading up to, and justifying, the incursion. I had to put up with some heckling in the State Department auditorium, but, by and large, the briefings went well, since we were assisted by a lot of “factual” information supplied by our intelligence regarding enemy losses of ammo dumps and the like in sanctuary areas.

But the Senate, especially the SFRC, reflecting the angry mood of the media and campuses, finally passed the Cooper-Church amendment on June 30 [it sought to cut off all funding to American war efforts in Cambodia. This was the first time Congress restricted the deployment of troops during a war against the wishes of the president.] By then, a reluctant Nixon had already ordered the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Cambodia. I suspect Rogers had some influence on that decision.