Following Allied victory in World War II, the world plunged headfirst into a bitter rivalry lasting decades between the two superpowers of the time: the United States and the Soviet Union. The U.S. and the USSR strived for superiority in the buildup of nuclear weapons, the space race, and the ability to exert ideological influence on other nations.

The 1970s, however, marked a turning point with the introduction of a period of détente, or an easing of strained relations, between the two entities. Individuals in both countries began to advocate for the opening of security negotiations that would facilitate the easing of tensions between the battling states.

In July 1973, thirty-five nations began talks under the framework of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). Talks continued in Geneva until 1975, after which the participants reconvened in Helsinki on August 1, 1975 to sign the Helsinki Final Act. This agreement became known as the Helsinki Accords, which served as the groundwork for the later Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), established in 1995 under the Paris Charter of 1990.

The Helsinki Final Act tackled a variety of issues which were divided into “baskets.” The first basket (security dimension) dealt with an array of military and political issues, such as the definition of borders in a Europe plagued by war and competing political philosophies. The second (economic dimension) emphasized the importance of active trade, protecting the environment, and other economic issues. The third (human dimension) focused on human rights, including freedom of emigration and freedom of the press. Finally, the fourth and final basket defined the details of a follow-up meeting and implementation measures. The passage of the act led to greater cooperation between Western and Eastern Europe and contributed to significant political and social changes in Europe.

Although the Soviet Union was expected to present the biggest challenge, the talks were complicated by an unforeseen voice of disapproval: the Maltese Prime Minister Dom Mintoff. Mintoff pressed for the inclusion of the Mediterranean region into the measures being discussed and the gradual withdrawal of Soviet and American forces from the greater Mediterranean region. Following his threat to use a veto, which would have prevented the passage of the act, the “Mediterranean Chapter” was added, in which signatories stated that “security in Europe . . . is closely linked with security in the Mediterranean.”

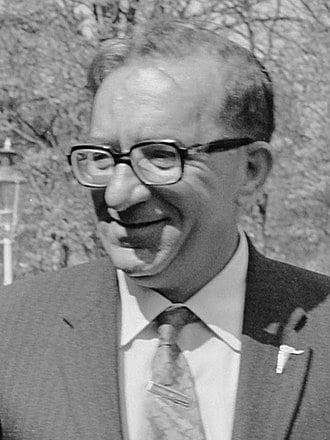

The U.S. delegation found an unexpected ally in its negotiations with the Maltese: the Soviets. FSO George Jaeger was a participant in the negotiations while serving in Geneva, Switzerland. He was approached by Soviet Ambassador Lev Mendelevich, who proposed the collaboration of the two countries in discussions with the Maltese. In this “moment” in U.S. diplomatic history, Jaeger learns the art of Soviet diplomacy.

More Moments in U.S. Diplomatic History

Jaeger’s interview was conducted by Robert Daniels on July 9, 2000.

Read Jaeger’s full oral history HERE.

https://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Jaeger,%20George.toc.pdf?_ga=2.94836060.1918868774.1599057897-951479370.1590796792

Read more about Jaeger’s discovery of the Nazis’ Hadamar Camp HERE.

Read more about Jaeger’s experiences in pre-Anschluss Vienna HERE.

Drafted by Sophie May

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“This became all the more tricky, as we will see, because all CSCE (Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe) decisions had to be unanimous.”

The Emergence of a Mediterranean Declaration: Let’s first set the stage for what turned out to be a hilarious denouement, in which we ended in cahoots with the Soviets trying to deal with Malta—and failed!

From the outset, even in the preparatory talks in 1973, there was pressure from the European Mediterranean states that the Mediterranean region should have some distinct status and that part of the Final Act should be devoted to it.

Initially there were battles over who was to be recognized as a Mediterranean state—since the Maltese pressed for the inclusion of Algeria and Tunisia, which in turn raised the question of all the other littoral states, including Israel.

The solution arrived at with some difficulty allowed all such non-participating states to make written presentations to the preparatory CSCE meeting, proposing agenda items and questions relating to Baskets I and II, but not Basket III, which would have opened the door to discussion of the emigration of Soviet Jews to Israel.

These issues arose again early in the Geneva phase when the Mediterranean member states again pressed for agreement to allow the non-participating states to return for follow-up questions and explanations, which was, very reluctantly, granted. In short, there were north-south divisions at the conference from the outset which required careful tending so that they would not distract from or impede the major east-west issues the Helsinki process was primarily meant to deal with. This became all the more tricky, as we will see, because all CSCE decisions had to be unanimous.

Later, in June ‘74, the nine European Community states—led by Italy, France and Malta—tabled a joint ‘Mediterranean Declaration’, which the U.S. at first resisted, fearing that it would introduce the Israel-Arab dispute into this already highly complicated conference; but then accepted, after the Europeans appealed to Kissinger, stressing the importance of their relations with the Arabs. This in turn resulted in the creation of the Mediterranean working group on which I was to sit, and prompted the introduction of an even more ambitious draft by the Maltese.

“He [the Maltese Ambassador] warned us again and again that Malta’s Prime Minister, Dom Mintoff, was utterly serious and not bluffing.”

No Backing Down: Even so, the Mediterranean issue did not come center stage until late April or early May 1975, after I had just joined the working group. After agreement had finally been reached on a long but anodyne Preamble to the eventual text, the Maltese dropped their bombshell—calling for language that would establish special links between the Mediterranean states and the Arab world and require the gradual withdrawal of Soviet and American forces from the Mediterranean area!

At first, all of us largely ignored this proposal, which was just as unwelcome to the Soviet Bloc as to the Western powers. We all assumed it was being made for the record and would in due course be withdrawn.

However, as time pressure to finish the negotiations mounted in June, Malta’s Ambassador Victor Gauci, a dear and kindly diplomat who understood the situation perfectly, warned us again and again that Malta’s Prime Minister, Dom Mintoff, was utterly serious and not bluffing. By the end of June the Maltese tone hardened further, as Gauci made clear on instruction that Mintoff was prepared to withhold Malta’s consent to the Final Act, in effect sinking the Helsinki process since unanimity was required, until his demands were met. The mouse had roared!

Q: Well that must have put the cat among the pigeons!

JAEGER: And how! Efforts were of course made to meet the Maltese part way with broad language encouraging ‘better relations with the non-participating states’, including ‘all states in the Mediterranean’. But Mintoff remained unimpressed and responded by having his representative block the follow-on agreement as well. It was now clear that the Helsinki process hung in the balance and that all of us, east and west, were facing a fulldress crisis.

“ Let me teach you the first Soviet principle of negotiation!”

The Pivotal Role of Food: After a final appeal was made to Dom Mintoff, he sent a team of four Maltese Ambassadors to Geneva on July 10 who, together with Ambassador Gauci, were to meet with five diplomats representing the Mediterranean Working group. I was asked to be the American negotiator.

The meeting in the Conference Center was to begin at 7:00 p.m. I went there at about five-thirty and ran into Soviet Ambassador Lev Mendelevich, a rotund Jewish gentleman, who was my Soviet counterpart. Mendelevich hailed me with a touch of sarcasm, “Ah, Meester Jaeger. I suppose you are well prepared for this negotiation.” I said, “Well, you know, we have our positions, and I think we’re prepared.” Mendelevich went on the offensive, “I don’t think so at all. Have you eaten?” Somewhat taken aback, I said, “Well, no, but I expect there’ll be a sandwich or something.”

He said, “I thought so! Let me teach you first Soviet principle of negotiation! Make sure Soviet representation eats so that we will be strong, and the other side does not eat, therefore hungry and weak. America and the USSR are partners this time in dealing with these Maltese. The Maltese are flying in late, won’t have had time to eat. So let’s go to the restaurant together and eat!”

We did, but only found a forlorn-looking waiter setting tables who told us the restaurant was closed. Mendelevich was undeterred, shouted at the poor wretch that he was an Ambassador of the USSR and asked that the manager be sent for. When the latter appeared a few minutes later, and again tried to explain that the restaurant was closed, Mendelevich went into a table-banging tantrum and, as a small crowd of onlookers gathered around, threatened the manager with an official complaint from the USSR which would get him fired! The manager got the point, rousted out a crew and a few minutes later served us a hearty meal.

“I will tell them that they’re representatives of a totally insignificant, irrelevant little country, that they are being objectionable and that their positions are an affront and make no sense.”

Gameplan: When we had finished, Mendelevich, again in high good humor, said, “OK. Now we have taken care of our bodies. What’s your plan for winning in this negotiation?” I said, “Well, I guess we’ll see what they have to say, and then advance our positions. It will help that this time you and I will be in agreement.” “Yes indeed”, Mendelevich said, “But how are we going to wear them down?”

“Here”, he continued, “is the game plan. I will play the bad guy as usual, and you will be the good guy. When the five Maltese Ambassadors come in, I will begin to insult them. Then, as the talks get under way, I will insult them some more. I will tell them that they’re representatives of a totally insignificant, irrelevant little country, that they are being objectionable and that their positions are an affront and make no sense. After this has gone on for a while, and they are upset, you will intervene and say, ‘Mr. Soviet Ambassador, you are being a little bit strong with these nice friends of ours. Don’t you think that a little politer tone might get us a further in this discussion?’” Then Mendelevich got to the point. “Each time we go through this, they will make a small concession because they will be so grateful to you. We will keep this up as long as necessary until we win. This”, he concluded,” is Soviet negotiating method. It always works.”

Q: Not totally new to people who’ve dealt with the Russians, but fascinating that he would lay it out for you!

“Well, so much for Soviet diplomacy, eh?”

The Aftermath:

JAEGER: Well, we tried it his way. The Maltese came, Mendelevich was rude to them and got more and more insulting as the evening went on. I played the good guy and our British colleague soon joined in, appealing to him to moderate his insulting behavior. And you know what? The Maltese didn’t budge an inch! Not one inch!

Q: So his game plan didn’t work?

JAEGER: It got to be eleven o’clock, then midnight. Everybody was getting tired and the Maltese were increasingly annoyed as Mendelevich kept escalating his insults and abuse. At one o’clock the Maltese head of delegation said, “We have had enough. We’re going home. Good night gentlemen. This is the end of the discussion,” and walked out.

I couldn’t help but turn to Mendelevich and say, “Well, so much for Soviet diplomacy, eh?”

Q: So how was it all resolved?

JAEGER: What I, at least, didn’t know was that Kissinger and Gromyko were also meeting in Geneva that night, and, as Maresca reports in his book, heard Kovalev, the Head of the Soviet Delegation, argue that, since the Maltese could not be permitted to hold the Helsinki process hostage, they should simply be isolated and cut out.

Kissinger then asked Ambassador Sherer for his view. Sherer argued to the contrary that the principle of unanimity was so central to the CSCE, that breaking it would only lead others to side with the Maltese and undermine the whole process.

The next day, the Maltese, under continuing high-level pressure, agreed to accept the palliative paragraph they had been offered, provided the phrase “reducing armed forces in the region” was added as an additional objective of contacts with non-participating states. It was the same poison pill in new language!

Since Mintoff held all the cards, the U.S., the USSR and all the other delegations were in the end instructed to swallow their objections and accept Mintoff’s language—with the agreed mental reservation that it would just never be put in practice. So the Helsinki process was saved and the ignominiously agreed text made part of the Final Act under “Questions relating to Security and Cooperation in the Mediterranean”. Paragraph 412 contains the Conference’s concession to Dom Mintoff’s blackmail. The road was cleared to Helsinki, where the Final Act was solemnly adopted on July 30.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in St. Vincent’s College 1944–1948

Program for International Affairs, Harvard University 1948–1951

Joined the Foreign Service 1958

Zagreb, Yugoslavia—Political Officer 1961–1964

Bonn, Germany—Political Officer 1967–1970

Paris, France—Political Officer 1975–1978

Brussels, Belgium—Deputy Assistant Secretary General of NATO for Political Affairs 1984–1987